|

|

|

|

I found this lovely wish for the New Year: “I hope that your life flows

calmly, but not too much so you get bored; that it has the right emotions

but not too much to make you suffer; that it has the right amout of

suffering to make you grow but not too much to destroy you; and that

there is all the love possible, which can never be too much.”

Saturday, December 28, 201

|

|

Ho trovato questo bellissimo augurio natalizio e vorrei condividerlo: “Vi

auguro che questa stella di Natale resti accesa ogni giorno, tutti i giorni

dell’anno. Che possa illuminare e guidare i vostri passi nei giorni più bui,

e che quella luce speciale che fa brillare i vostri cuori non si spenga mai.”

|

I found this lovely Christmas wish and I would like to share it with you:

“I wish that this Christmas star remain lit every day, every day of the

year. That it may light and guide your steps in the darkest days; and

that the special light that shines in your heart may never go out.”

Saturday, December 21, 2019

|

|

Vi s DIZIONARIO O VOCABOLARIO? Vi s DIZIONARIO O VOCABOLARIO?

Vi siete mai posti questa domanda? Nel linguaggio comune i termini

“vocabolario” e “dizionario” sono interscambiabili, ma in realtà non

sono propriamente dei sinonimi, ed un’analisi più attenta porta a

notare delle differenze che possono chiarirne meglio anche l’uso

nei diversi contesti.

Sul modello delle coppie francese dictionnaire/vocabulaire e inglese

dictionary/vocabulary, nell'italiano di fine Novecento si è affermata

una distinzione tra vocabolario inteso come “insieme di vocaboli

propri di una lingua, di un dialetto, di una varietà settoriale o anche

di un individuo” (il vocabolario italiano, il vocabolario medico, il

vocabolario dannunziano) e dizionario inteso come “opera

lessicografica” (il dizionario italiano-inglese, il dizionario dei sinonimi

e contrari, il dizionario dei proverbi, il dizionario etimologico…).

Quindi, come conferma anche l’Accademia della Crusca, un

“dizionario è più esteso di un vocabolario in quanto si può riferire

a trattazioni disposte in ordine alfabetico, ma non propriamente

lessicali”.

Ma mentre nell’accezione di dizionario non può assolutamente

essere utilizzato il termine vocabolario, è tuttavia possibile il

contrario, anche perché sempre più spesso nei vocabolari sono

presenti locuzioni che sarebbero proprie di un dizionario. Ecco

perché i due termini vengono solitamente utilizzati come sinonimi

nel linguaggio comune e anche noti vocabolari della lingua italiana

si definiscono nei loro titoli “Dizionario della Lingua Italiana” (ad

esempio, De Mauro, Devoto-Oli, Garzanti).

Rimangono invece fedeli alla definizione di vocabolario la Treccani

e la Zanichelli col suo Zingarelli.

http://makalanguageconsulting.blogspot.com/2015/12/che-

differenza-ce-tra-vocabolario-e.html

I found the above entry on line at

http://makalanguageconsulting.blogspot.com

/2015/12/

che-differenza-ce-tra-vocabolario-e.html

It refers to an article written for the Accademia della Crusca

website on June 19, 2009, by Luca Serianni in which the author

addresses the difference between “vocabolario” and “dizionario”.

Here is my translation of the most important parts of Professor

Serianni’s article: In a lucky little volume entitled What is a

“vocabolario” (Florence, Le Monnier Publishers, 1961), Bruno

Migliorini, the great linguis t, address this question in his opening

statements to the book…There used to be a distinction between

vocabolario, a collection of words and dizionario a collection of

words and locutions (someone may have even proffered the

opposite). A dictionary is more extensive in that it can refer to

treatments in alphabetical order but nor properly lexical, we can say

Biographical Dictionary but not a Biographical vocabolario. Basing

itself on the French and English models, in Italy at the end of the

20th century a distinction between dizionario as a lexicographic

work and vocabolario as a complex of words and locutions belonging

to a language, a dialect belonging to an area or even to an individual:

medical vocabolario, the exuberance of the vocabolario of Gabriele

D’Annunzio,…In the titles of the great lexicographic works of

contemporary Italian the term dizionario dominates, except for the

stalwarts still use vocabolario.

Saturday, December 17, 2019

|

|

Ma dai…

È una di quelle espressioni usate spesso, ma continua a confondere gli

studenti. Vediamo cosa può significare:

Approvazione:

Cristina: “Ho finalmente finito la tesi.”

Giuseppe: “Ma dai…complimenti!”

Incoraggiamento:

“Ma dai, assaggia questi tartufi bianchi, vedrai che ti piaceranno; ma stai

attenta se ti piacciono troppo ti potrai ridurre sul lastrico.”

Fastidio:

“Ma dai, smettila di gironzolarmi intorno!”

Sorpresa:

Susanna: “Ho smesso di fumare.”

Caterina: “Ma dai!”

Irritazione:

“Ma dai Giorgio, ti ho capito la prima volta, basta così, non devi continuare

a ripetere le stesse cose!”

Esasperazione:

“Ma dai…come fai a non capire, te l’ho spiegato almeno dieci volte!”

Incredulità:

Elena: “Ieri ho vinto la lotteria, e domani mi comprerò quella Ferrari che

ho sempre desiderato.”

Teresa: “Ma dai?”

E allora, come si traduce

So, how do we translate it?

It is one of those expressions that is used all the time but continues

to confuse students. Let’s take a look at what it can mean:

Approval:

Cristina: “I finally finished by thesis.”

Giuseppe: “Wow…congratulations!”

Encouragement:

“Come on, taste these white truffles, you’ll see you’ll like them; but be

careful, if you like them too much you’ll break the bank.”

Annoyance:

“Come on, stop hanging around me!”

Surprise:

Susanna: “I quit smoking.”

Catherine: “Come on, I’ll be…”

Irritation:

“Okay George, I understood you the first time, that’s enough, you don’t

have to repeat the same things over again.”

Exasperation:

“Come on, how is it you don’t understand, I explained it at least ten

times.”

Incredulity:

Christine: “Yesterday I won the lottery, and tomorrow I will buy that

Ferrari that I always wanted.”

Teresa: “Oh really?”

Saturday, December 7, 2019

|

|

Il Giorno del ringraziamento, o più semplicemente "il Ringraziamento", è

una festa di origine cristiana osservata negli Stati Uniti d'America (il

quarto giovedì di novembre) e in Canada (il secondo lunedì di ottobre) in segno di gratitudine per il raccolto e per altre benedizioni ricevute

durante l'anno trascorso.

Il “primo Thanksgiving” fu celebrato dai Pellegrini nell’ottobre del 1621

dopo il primo raccolto. La festa durò per tre giorni, se secondo uno dei

partecipanti, Edward Winslow, ci furono 90 Nativi Americani e 53

Pellegrini

Anche se non si celebra in Italia, possiamo trovare qualcosa o qualcuno di cui essere grati, perciò vi auguro un Felice Giorno di Ringraziamento!

Thanksgiving Day or just plain Thanksgiving is a feast day with Christian

roots which is celebrated in the United State the fourth Thursday in

November and in Canada the second Monday in October as a sign of

thanks for the harvest and other blessings received during the past year.

The “first Thanksgiving” was celebrated by the Pilgrims in October of

1621 after the first harvest. The celebration lasted three days, and

according to Edward Winslow, one of the participants, there were 90

Native Americans and 53 Pilgrims present.

Even if it isn’t celebrated in Italy, we can find something or someone to be grateful for, thus I wish you a Happy Thanksgiving!

Saturday, November 23, 2019

|

|

MAGARI: una parola usata comunemente in italiano, ma non si

traduce facilmente.

Allora, cosa significa?

Magari è usata per esprimere:

1. Un desiderio: Hai comprato quell’appartamento che volevi?

Magari! C’era uno più ricco di me.

2. Sì per favore/grazie: Caterina ed io andiamo fuori a cena questa

sera,

prenoto un tavolo per tre?

Magari!

3. Se: Magari avessi studiato italiano invece di coreano, oggi sarei a

Firenze. Magari fossi ricca!

4. Forse: Magari invitiamo Lorenzo e Lisa a pranzo.

5. Piuttosto: Magari butto tutto nell’immondizia, ma loro non

avranno mai un soldo.

MAGARI: a word that is commonly used but just doesn’t translate

easily.

So, what does it mean?

Magari is used to express:

1. A desire: Did you buy the apartment you wanted?

I wish! There was someone richer than I.

2. Yes please/thank you: Caterina and I are going out for dinner this

evening,should I reserve a table for three?

Yes please.

3. If only: If only I had studied Italian instead of Korean, today I would

be in Florence.

If only I were rich!

4. Maybe/perhaps: Maybe we’ll invite Lorenzo and Lisa to dinner.

Instead/rather: I’d rather throw everything in the garbage, but they

won’t ever get a penny.

Saturday, November 16, 2019

|

|

SNACK, MERENDA, SPUNTINO?

C’è una differenza tra spuntino e merenda? In inglese c’è solo una parola

“snack” ma in italiano la risposta alla domanda è: Sì!

Uno spuntino è un pasto rapido e leggero, uno snack, che si fa tra i pasti

principali o a qualsiasi ora del giorno o della notte quando si ha fame. Per

esempio: Questa sera ceniamo tardi, a pranzo ho mangiato poco, ho

bisogno di uno spuntino o non arrivo alla cena.

La merenda può anche essere uno spuntino, ma di solito si fa tra il pranzo

e la cena, soprattutto da parte di ragazzi quando tornano dalla scuola. La

merenda si fa anche a metà mattina, specialmente da parte di scolari, i

bambini dell’asilo e delle scuole elementari. Questi sono di solito cibi non

cucinati, freddi che si possono mangiare con le mani.

Esiste anche la parola “merendina” che indica uno snack già confezionato

il quale è sia spuntino sia merenda.

Buon appetito, ma non mangiate troppo, ho preparato qualcosa di

speciale per la cena questa sera!

Is there a difference between the terms “spuntino” and “merenda”? In

English there is only one word “snack” but in Italian the answer to the

question is Yes!

“Spuntino” is a quick light meal consumed between main meals or at any

time of day or night when one is hungry. For example: This evening we

are eating late, at lunch I didn’t eat much, I need a “spuntino” or I won’t

make it to supper.

“Merenda” may also be considered a “spuntino” but it is usually eaten

between lunch and dinner, usually by children when they get home from

school. “Merenda” may also be eaten mid-morning, usually by

kindergarteners or elementary school children. These foods are not

cooked and served cold or at room temperature and can be eaten with

your hands.

There is also the term “merendina” (little merenda) which is a

prepackaged snack which may be eaten either as a “spuntino” or a

“merenda”.

Buon appetito, but don’t eat too much, I prepared something special for

dinner this evening!

Saturday, November 9, 2019

|

|

| |

HALLOWEEN È CALABRESE!?

Secondo quest’articolo che ho trovato sul giornale online, Calabria News:

Halloween è una tradizione calabrese.

“Ebbene sì la tesi è di Luigi Maria Lombardi Satriani, antropologo

calabrese e professore all’università Sapienza di Roma che ha descritto

l’usanza tipica di Serra San Bruno del “Coccalu di muortu” che si traduce

in “teschio di morto” in dialetto delle serre vibonesi. L’usanza di svuotare

una zucca, ricavarne tratti di un viso umano e porvi dentro una candela

risalirebbe quindi alla migrazione delle popolazioni meridionali in America

che avrebbero portato con loro e continuato a praticare una tradizione

dal significato antropologico ben preciso, ovvero stabilire un contatto con

i propri cari defunti. I bambini in giro per il paese con la zucca, chiedono

un’offerta con la frase tipica: “Mi lu pagati lu coccalu?” (Mi pagate il

teschio di morto?). La ricompensa è quasi sempre una piccola somma di

denaro che alla fine del giro i bambini dividono tra di loro per andare a

comprare qualche leccornia.”

According to this article I found on the online newspaper Calabria News:

Halloween is a tradition from the Italian region of Calabria.

And yes, this premise belongs to Luigi Maria Lombardi Satriani, Calabrese

anthropologist and professor at the University La Sapienza in Rome, who

described the typical tradition in Serra San Bruno of “Coccalu di muortu”

which translates into “skull of the dead” from the dialect of the mountains

near Avellino. The tradition to empty a pumpkin, draw a human face on it

and place a candle inside is traceable to the migration of individuals from

the southern part of Italy to America. They brought this tradition—which

has a specific anthropological meaning—with them and continued to

practice it; they wanted to establish contact with their dearly departed.

Children walk around town with a pumpkin, asking for an offering using

the sentence: “Mi lu pagati lu coccalu?” (In dialect this means, will you

pay for a skull?) The reward is almost always a small sum of money

which at the end of the day the children divide among

themselves to go and purchase some delicacies.

Saturday, November 2, 2019

|

|

Si dice avere senso o fare senso?

Una trappola linguistica è tradurre direttamente da una lingua all’altra.

Questo problema si presenta quando pensiamo all’inglese: “it makes

sense” e lo traduciamo letteralmente in italiano come “fa senso”.

Questo però è un errore. Fa senso significa che una cosa produce

simile alla ripugnanza o al disgusto; una specie di turbamento fisico o

psichico.

Per esempio: I serpenti mi fanno senso.

Le immagini di brutalità che si vedono in alcuni film oggigiorno fanno

senso. Avere senso significa che una situazione o un’idea ha un

contenuto logico, valido, giustificabile.

Per esempio: La spiegazione della professoressa ha senso, finalmente

capisco i verbi riflessivi.

Gina, non ha senso svegliarti alle 4, l’autobus turistico arriva alle 10,

cosa farai per quelle 6 ore?

How do we translate “it makes sense” into Italian? If we fall into the

trap of a literal translation we would say “fa senso”. This however is a

mistake. Fa senso means that something produces a strong and

unpleasant impression, similar to repugnance or disgust, a type of

physical or psychic turmoil.

For example: Snakes disgust me.

The images of brutality that are shown in some films these days are

repugnant.

Avere senso means that a situation or an idea has a logical, valid,

justifiable content.

For example: The explanation the professor gave makes sense, I

finally understand reflexive verbs.

Gina, it makes no sense to wake up at 4, the tour bus arrives at 10,

what are you going to do for those 6 hours?

Saturday, October 26, 2019

|

|

Che divertimento trovare una parola che ha tanti significati in entrambe

le lingue! Pensiamo alla parola “BUFF” in inglese, come si traducono i

suoi molti usi? Sostantivi:

1. Il colore giallo scuro; il colore di camoscio

2. Pelle scamosciata, panno scamosciato

3. Pelle di camoscio

4. Disco che pulisce il camoscio

5. Pelle nuda

6. Entusiasta, fanatico, appassionato

7. Genio, esperto

Aggettivi:

1. Giallo scuro, marrone chiaro

2. Di camoscio, scamosciato

3. Muscoloso, atletico, robusto

4. Bello, attraente

5. Lucido, lucidato

Verbi transitivi:

1. Lucidare, brillantare il metallo

2. Lucidarsi le scarpe

3. Scamosciare

What fun it is to find a word that has so many meanings in both

languages. Let’s look at the word “BUFF” in English, how can we

translate its many uses?

Nouns:

1. Dark yellow, the color of suede

2. Suede or chamois cloth

3. Suede

4. A disc that cleans suede

5. Naked skin—in the buff

6. Enthusiast, fanatic: movie buff, history buff for example

7. Genius or expert: she’s a computer buff

Adjectives:

1. Dark yellow or light brown

2. Of chamois or suede

3. Muscular, athletic, in shape

4. Handsome, attractive

5. Shiny, polished

Transitive verbs:

1. To polish metal

2. To shine shoes

To buff leather

Saturday, October 19, 2019

|

|

SI AUGURA “BUON FINE SETTIMANA” O “BUONA FINE SETTIMANA”?

Quest’espressione è attestata in italiano dal 1932.

Per rispondere cito dal sito dell’Accademia della Crusca: <<Quanto a la

fine settimana o il fine settimana anch’esso ambigenere, l’uso sembra

decisamente inclinare verso il genere maschile, forse per l’attrazione

esercitata da il (lo) week end da cui deriva, col genere femminile si

tende per lo più ad usare la fine della settimana.>>

Il modo più semplice è di augurare un buon

DO YOU WISH SOMEONE “BUON FINE SETTIMANA” OR “BUONA FINE

SETTIMANA” (in other words is it masculine or feminine)?

This expression is documented in Italian from 1932.

To answer I quote from the website of the Accademia della Crusca

(Italy’s ultimate grammar authority): “In regard to la fine settimana or

il fine settimana being also common-gender, the use tends decisively

towards the masculine. Perhaps due to the attraction of the English

term weekend from which it derives. The feminine is more commonly

used for the end of the week (la fine della settimana).”

Saturday, October 12, 2019

|

|

GLI AGGETTIVI INTERROGATIVI ED ESCLAMATIVI:

Parte II

GLI AGGETTIVI ESCLAMATIVI

Gli aggettivi interrogativi e gli aggettivi esclamativi sono

gli stessi: che, quale, quanto.

che, è invariabile e ha lo stesso significato di quale;

quale, varia nel numero ma non nel genere (quale/quali);

quanto, variabile sia nel numero che nel genere (quanto/

quanta/quanti/quante).

Gli aggettivi esclamativi si trovano in frasi che

terminano con un punto esclamativo.

Che macchina magnifica hai comprato!

Mamma mia, quale ristorante avete scelto, costa un

occhio della testa!

Michele, quanto vino hai bevuto! Domani soffrirai di mal

di testa.

INTERROGATIVE AND EXCLAMATORY ADJECTIVES:

Part II

EXCLAMATORY ADJECTIVES

Interrogative and exclamatory adjectives are the same in

Italian and they are: che (what/which), quale (what/which),

quanto (how much).

che, is invariable and has the same meaning as quale;

quale, varies by number but not by gender (quale/quali);

quanto, varies by number and by gender (quanto/quanta/

quanti/quante).

Exclamatory adjectives are found in sentences that end with an

exclamation point.

Saturday, October 4, 2019

|

|

AGGETTIVI ESCLAMATIVI:

Parte I

GLI AGGETTIVI INTERROGATIVI

Gli aggettivi interrogativi e gli aggettivi esclamativi sono gli stessi: che,

quale, quanto.

·che, è invariabile e ha lo stesso significato di quale;

·quale, varia nel numero ma non nel genere (quale/quali);

·quanto, variabile sia nel numero che nel genere (quanto/quanta/

quanti/quante).

Gli aggettivi interrogativi sono usati per introdurre una domanda, sia

in modo diretto, sia in quello indiretto. Domande dirette in forma

scritta terminano con il punto interrogativo, mentre quelle orali sono

espresse con un cambiamento di tono di voce. Le domande indirette

sono richieste sotto forma d’affermazione, usate spesso per essere

più cortesi.

Esempi di domande dirette:

Che macchina hai intenzione di comprare?

Quale ristorante è il tuo preferito? Quali piatti sono i migliori?

Al ristorante, quanto vino avete bevuto, quanti piatti avete ordinato,

quanta pasta avete mangiato, quante tazze di caffè avete bevuto?

Esempi di domande indirette:

Gianni vuole sapere che macchina hai intenzione di comprare.

Susanna vorrebbe domandarti quale ristorante è il tuo preferito e

quali piatti sono i migliori.

Sono curiosa di sapere al ristorante, quanto vino avete bevuto, quanti

piatti avete ordinato, quanta pasta avete mangiato, quante tazze di

caffè avete bevuto.

NOTATE che le domande dirette terminano con un punto

interrogativo, quelle indirette con un semplice punto.

INTERROGATIVE AND EXCLAMATORY

ADJECTIVES: Part I

INTERROGATIVE ADJECTIVES

Interrogative and exclamatory adjectives are the same in Italian and

they are: che (what/which), quale (what/which), quanto (how

much).

- che, is invariable and has the same meaning as quale;

- quale, varies by number but not by gender (quale/quali);

- quanto, varies by number and by gender (quanto/quanta/

quanti/quante).

Interrogative adjectives are used to introduce a question, directly and

indirectly. Direct questions in written form end with question mark,

spoken questions are expressed with a change in tone. Indirect

questions are requests in the form of a statement, often used to be

more polite.

Examples of direct questions:

Which car are you going to buy?

Which restaurant is your favorite? Which are the best dishes?

At the restaurant, how much wine did you drink, which dishes did you

order, how much pasta did you eat, how many cups of coffee did you

drink?

Examples of indirect questions:

Gianni would like to know which car you are going to buy.

Susanna would like to ask you which restaurant is your favorite and

which are the best dishes.

I’m curious to know at the restaurant, how much wine did you drink,

which dishes did you order, how much pasta did you eat, how many

cups of coffee did you drink.

Please note that direct questions end with a question mark, indirect

ones with a simple period.

Saturday, September 28, 2019

|

|

| AGGETTIVI |

ADJECTIVES

|

| che indicano un periodo di tempo: |

that indicate a period of time:

|

| Giornaliero: |

Daily: |

mattutin

pomeridiano

serale

notturno

|

morning

afternoon

evening

notturno night/nocturnal |

Stagionale:

estivo

autunnale

invernale |

Seasonal:

spring-like

summery

autumnal

wintery

|

Tempo:

orario/per ora

giornalieroweeklymensile

bimensile (due volte al mese)

bimestrale (che dura due mesi)

bimestrale (ogni due mesi)

trimestrale

semestrale

annuale

biennale

triennale

quinquennale

decennale

centennale |

Time:

hourly

daily

weekly

monthly

bimonthly/twice-monthly

bi-monthly/lasting two months

bi-monthly/every two months

quarterly/three-monthly

biannual/semiannual

annual

biennial/two-year

triennial/three-year

quinquennial/five-year

decenn period of time:ial/

every ten years

centennial

|

|

Saturday, September 14, 2019

|

|

QUIN

DI

Di recente in classe abbiamo ripassato delle espressioni che non si

traducono facilmente in inglese; espressioni che hanno un significato

o un uso particolare. Eccone un’altra. Per la definizione qui riportata

mi sono riferita al dizionario online del CORRIERE DELLA SERA.

QUINDI [quìn-di] avverbio, congiunzione

1. Avverbio: letterario Di qui, di lì: “E quindi uscimmo a riveder le

stelle” (Dante Alighieri, La Divina Commedia, Inferno, Canto

XXXIV, 139)

2. Congiunzione

a. Con valore deduttivo-conclusivo, perciò, di conseguenza, per

questo motivo, dunque: Ero piuttosto nervoso, quindi ho preferito

evitare discussioni; Il tempo è pessimo, dobbiamo quindi rinunciare

alla gita; con lo stesso valore opera, come congiunzione, tra due

termini della stessa frase: È una persona distratta, quindi inaffidabile

|| E quindi?, in un dialogo per sollecitare una deduzione, nel

significato di “e con ciò?”, “e allora?”

b. Con valore temporale, poi; successivamente: Percorri la strada

fino in fondo, quindi gira a sinistra; “Diede una rassettata alle

coperte spiegazzate. Quindi uscì sulla terrazza” (Alberto Moravia

Gli indifferenti)

3. sec. XIII

In class recently we reviewed several expressions that do not

translate easily into English; expressions that have a particular

meaning or use. Here is another one. The Italian definition used

here is taken from the online dictionary of the Corriere della Sera.

QUINDI: adverb, conjunction

1. Adverb: literary, from here, from there: “And thence we came

forth to behold the stars once more.” (The final verse of Dante

Alighieri’s Inferno)

2. Conjunction

a. In a deductive-concluding sense it means: therefore, as a

consequence of, for this reason, thus: I was quite nervous,

therefore [quindi] I preferred to avoid any arguments; The

weather is awful, therefore [quindi] we have to give up on taking

the trip. In a similar way it functions as a conjunction between two

expressions in the same sentence: He’s distracted, therefore

[quindi] unreliable // And therefore [quindi/then] In a dialogue,

to solicit a conclusion, meaning “and? Meaning what?”, “and then?”

b. With a temporal value, then, at a later time: Follow the road to

the end, then [quindi] turn left. “She tidied up the crumpled covers,

then [quindi] she went out on the terrace.” Alberto Moravia.

This word became part of the Italian language during the 13th

century.

Saturday, September 21, 2019

|

|

|

| AGGETTIVI |

ADJECTIVES

|

| che indicano un periodo di tempo: |

that indicate a period of time:

|

| Giornaliero: |

Daily: |

mattutin

pomeridiano

serale

notturno

|

morning

afternoon

evening

notturno night/nocturnal |

Stagionale:

estivo

autunnale

invernale |

Seasonal:

spring-like

summery

autumnal

wintery |

Tempo:

orario/per ora

giornalieroweeklymensile

bimensile (due volte al mese)

bimestrale (che dura due mesi)

bimestrale (ogni due mesi)

trimestrale

semestrale

annuale

biennale

triennale

quinquennale

decennale

centennale |

Time:

hourly

daily

weekly

monthly

bimonthly/twice-monthly

bi-monthly/lasting two months

bi-monthly/every two months

quarterly/three-monthly

biannual/semiannual

annual

biennial/two-year

triennial/three-year

quinquennial/five-year

decenn period of time:ial/

every ten years

centennial

|

|

|

L’AVVERBIO GIÀ HA VARI USI:

1. Indica un evento compiuto o accaduto in un passato prossimo

o recente: Esempi: Quando Girolamo è arrivato alla stazione, il

treno era già partito. Ho troppo da fare; così ieri ero già in ufficio

alle sei del mattino.

2. Indica un evento che non occorre per la prima volta al passato:

Esempi: “Piacere di fare la Sua conoscenza, Dottor Marcantonio

ma credo che ci siamo già incontrati l’anno scorso alla conferenza

a Ferrara.” Vorrei un altro piatto di spaghetti, anche se ne ho già

mangiato uno, ho una fame da lupo.

3. Indica una previsione o una certezza futura: Esempi:

Margherita sa già come andrà a finire con i suoi, litigheranno e si

separeranno. Lina legge spesso i romanzi rosa, anche se sa già

come finiranno.

4. Quando già è usato da solo, indica essere in accordo: Esempio:

Lorenzo dice: “Quel film era eccezionale!” Elissa risponde: “Già,

veramente straordinario.”

THE ADVERB GIÀ IS USED IN VARIOUS WAYS:

1. It indicates an event that ended or happened in a recent past:

Examples: When Girolamo arrived at the station, the train had

already left. I have too much to do, so yesterday I was already in

my office by six a.m.

2. It indicates an event that doesn’t take place for the first time in

the past: Examples: “Pleased to meet you, Doctor Marcantonio,

but I believe we already met last year at the conference in

Ferrara.” I would like another plate of spaghetti, even if I already

ate one, I’m starving.

3. It indicates a prediction or future certainty:

Examples: Daisy already knows how it’s going to end up with her

parents, they’ll fight and separate. Lina often reads romance

novels, even if she already knows how they are going to end.

4. When già is used alone, it indicates agreement: Example:

Lawrence says: “That movie was exceptional!” Elissa answers:

“Già, (yes) really extraordinary.”

Saturday, September 7, 2019

|

|

Continuiamo il nostro studio degli indefiniti iniziato due

settimane fa.

Gli indefiniti indicano oggetti, persone, quantità non specifiche;

possono essere aggettivi, pronomi e/o avverbi. Piano piano,

affronteremo i vari tipi, ma ci vorrà del tempo e della pazienza.

PARTE III PARTE III

Alcuni aggettivi indefiniti hanno solo funzione aggettivale e

sono invariabili, altri si usano solo nella forma singolare e altri,

come tutti gli aggettivi, concordano con il numero e ilgenere del

nome cui riferiscono.

E non dimentichiamo questi aggettivi variabili:

Altro: Esempi: Come ha detto Scarlett O’Hara, domani sarà un

altro giorno.

Ogni giorno ci regala un’altra esperienza.

L’avvocato ha bisogno di altri documenti.

Vorrei indossare delle altre scarpe, queste sono troppo strette.

Certo: Esempi: Chiara cerca un certo tipo di lavoro.

Giacomo è andato alla festa di una certa amica, credo che si

chiami Rita.

Giovanna si è messa in certi guai, speriamo bene!

Certe giornate gli pesano.

Quale: Esempi: Dottoressa Martini, quale ristorante preferisce

al centro?

Quale rivista leggi adesso?

Quali formaggi hai comprato per la cena di domani?

Quali città visiterete durante la vacanza?

Let’s continue our study of the indefinites begun two weeks

ago.

Indefinites indicate objects, persons, quantities that are not

specified; they can be adjectives, pronouns and/or adverbs.

Slowly, we will look at the various kinds, but it will take time

and patience.

INDEFINITE ADJECTIVES-PART III

Several indefinites only have an adjectival use and are

invariable, others are used only in the singular, and others,

like all other adjectives, agree in number and gender with

the noun the modify.

So, let’s not forget these variable adjectives:

Altro/(an)other: Examples: As Scarlett O’Hara said: “After

all, tomorrow is another day!”

Every day gives us another experience.

The attorney needs other documents.

I would like to wear other shoes, these are too tight.

Certo/certain: Examples: Chiara is looking for a certain kind

of job.

Giacomo went to a certain friend’s party, I think her name is

Rita.

Giovanna is in quite a mess, let’s hope for the best!

Some days weigh on him.

Quale/which: Examples: Dr. Martini, which restaurant do

you prefer in town?

Which magazine are you reading now?

Which cheese did you buy for tomorrow’s dinner?

Which cities will you visit during your vacation?

Saturday, August 31, 2019

|

|

La settimana scorsa abbiamo incominciato il nostro studio

degli indefiniti, continuiamolo insieme.

Gli indefiniti indicano oggetti, persone, quantità non specifiche;

possono essere aggettivi, pronomi e/o avverbi. Piano piano,

affronteremo i vari tipi, ma ci vorrà del tempo e della pazienza.

PART II PART II

Alcuni aggettivi indefiniti hanno solo funzione aggettivale e sono

invariabili, altri si usano solo nella forma singolare e altri, come

tutti gli altri aggettivi concordano con il numero e il genere del

nome cui riferiscono.

Alcuni indicano una singola quantità:

Molto/Tanto: Esempi: Non ho molto/tanto tempo.

Mario è a dieta, non mangia molta/tanta pasta a pranzo, vuole

dimagrire.

Gemma è andata a fare la spesa ieri, e ha comprato molti/tanti

pasticcini.

La Dottoressa Andreini ha molte/tante amiche.

Parecchio: Esempi: Sfortunatamente ho parecchio da fare e non

posso uscire con voi.

Renato ha sprecato parecchia carta, la sua stampante era

guasta.

Isabella ha letto parecchi libri durante la sua convalescenza.

Tina ha piantato parecchie rose nel suo giardino.

Poco: Esempi: Irene ha poco spazio nei cassetti; compra troppe

cose.

Michele ha poca pazienza con i figli.

Dopo l’università, mi sono rimasti pochi soldi in banca.

Confronto all’anno scorso, ha ricevuto poche cartoline di auguri.

Troppo: Esempi: Pietro ha troppo tempo libero, si annoia,

dovrebbe fare del volontariato.

Il loro figlio ha troppa energia, è stancante fargli da babysitter.

Ci sono troppi libri sulla libreria, sta per cedere.

Questi giorni ho troppe cose da fare.

Last week we began our study of infinitives, let’s continue.

Indefinites indicate objects, persons, quantities that are not

specified; they can be adjectives, pronouns and/or adverbs.

Slowly, we will look at the various kinds, but it will take time

and patience.

INDEFINITE ADJECTIVES-PART II

Several indefinites only have an adjectival use and are

invariable, others are used only in the singular, and others, like

all other adjectives, they agree in number and gender with the

noun the modify.

Some adjectives refer to a singular quantity:

Molto/Tanto: a lot/many/much: Examples: I don’t have a lot of

time.

Mario is on a diet, he doesn’t eat much pasta for lunch; he

wants to slim down.

Gemma went grocery shopping yesterday and bought many

pastries.

Dr. Andreini has many friends.

Parecchio: a lot/many: Examples: Unfortunately I have a lot to

do and I can’t go out with you.

Renato wasted a lot of paper, his printer is broken.

Isabella read many books during her convalescence.

Tina planted many roses in her garden.

Poco/little/few: Examples: Irene has little space in her

drawers, she buys too much.

Michael has little patience with his children.

After university, I have little money left in the bank.

Compared to last year, she received few birthday cards.

Troppo/too much/too many: Examples: Peter has too much

free time, he gets bored, he should do some volunteer work.

Their son has too much energy, it’s exhausting being his

babysitter.

There are too many books on the shelf, it’s about to give way.

These days I have too many things to do.

Saturday, August 24, 2019

|

|

Che ne dite, apriamo un vaso di Pandora? Perché no?

GLI INDEFINITI!

Gli indefiniti indicano oggetti, persone, quantità non specifiche;

possono essere aggettivi, pronomi e/o avverbi. Piano piano,

affronteremo i vari tipi, ma ci vorrà del tempo e della pazienza.

Allora, incominciamo con gli aggettivi!

LI AGGETTIVI INDEFINITI-PARTE I

Alcuni indefiniti hanno solo funzione aggettivale e sono

invariabili, altri si usano solo nella forma singolare e altri, come

tutti gli aggettivi concordano con il numero e il genere

del nome

cui riferiscono.

1. Gli aggettivi indefiniti invariabili sono:

Qualche: Qualche volta preferisco andare in palestra; altre

volte fare una passeggiata lungomare.

Qualunque/Qualsiasi: Qualunque/Qualsiasi colore tu scelga per

tappezzare il divano, per me va bene, tranne l’arancione, si

capisce.

Ogni: Ogni volta che entro in quella profumeria mi viene il mal

di testa.

2. Certi aggettivi indefiniti hanno solo la forma singolare:

Alcuno: Non ho alcun dubbio, mi sono innamorata di Andrea.

Ciascuno: Ciascuna persona che entra, deve pagare il prezzo

fisso, non ci sono sconti oggi.

Nessuno: Nessuno studente ha superato l’esame, che disastro!

ATTENZIONE: questi aggettivi sono usati proprio come gli

articoli indefiniti: un, uno, una, un’. Forse sarebbe una buona

idea ripassarli.

What do you think, should we open Pandora’s box?

Why not? Indefinites!

Indefinites indicate objects, persons, quantities that are not

specified; they can be adjectives, pronouns and/or adverbs.

Slowly, we will look at the various kinds, but it will take time and

patience. So, let’s start with adjectives.

INDEFINITE ADJECTIVES-PART I

Several indefinites only have an adjectival use and are

invariable, others are used only in the singular, and others,

like all other adjectives agree in number and gender with the

noun the modify.

1. Invariable indefinite adjectives are:

Qualche: Some: Sometimes I prefer to go to the gym, others

to take a walk along the shore.

Qualunque/Qualsiasi: Any/whichever color you choose to

recover the sofa is fine with me, except orange, of course.

Ogni: Each time I enter that perfume shop, I get a headache.

2. Some indefinite adjectives have only a singular form:

Alcuno: Not any: I have no doubt that I’m in love with Andrew.

Ciascuno: Each person who enters, must pay the fixed price,

there are no discounts today.

Nessuno: No one: Not one student passed the exam, what a

disaster!

CAREFUL: these adjectives are used just like the indefinite

articles: un, uno, una, un’. Perhaps it would be a good idea to

review them.

Saturday, August 17, 2019

|

|

NIPOTE = NIECE, NEPHEW, GRANDDAUGHTER OR

GRANDSON?

Perché l’italiano non ha due (o più) termini diversi per indicare

i figli/le figlie dei figli/delle figlie o i figli/le figlie dei fratelli/

delle sorelle? È anche da ricordare che la parola nipote è

ambigenere, e solo l’articolo consente la distinzione tra maschi

e femmine.

Mi rivolgo all’Accademia della Crusca per la risposta:

“Probabilmente, il fatto che l’italiano non distingua tra due

gradi di parentela, che pure sono certamente diversi, si lega

all’organizzazione familiare tra Tardo Antico e Alto Medioevo,

che equiparava i diritti e i doveri di nonni e zii nei confronti dei

figli dei fratelli o dei figli e viceversa. Ricordiamo che nel latino

classico il maschile nepos e il femminile nepis indicavano solo i

figli del figlio o della figlia e la loro estensione al posto di filius/

filia fratis o sororis risale all’epoca imperiale.”

Per non confonderci allora possiamo sempre dire la figlia di

mio figlio (=mia nipote) o la figlia di mia sorella (=mia nipote).

L’inglese è più specifico in questi riguardi.

NIPOTE = NIECE, NEPHEW, GRANDDAUGHTER OR

GRANDSON?

Why is it that Italian doesn’t have two (or more) different

words to indicate the sons/daughters of sons/daughters or

the sons/daughters of brothers or sisters? It is also

important to remember that the word nipote has a common

gender (neither feminine nor masculine), and only the article

allows the distinction between boys and girls.

I turn to the Accademia della Crusca for the answer:

“Probably, the fact that Italian doesn’t distinguish between

the degrees of relatives that are certainly different, is tied to

the organization of the family between the Late Ancient

Period and the High Middle Ages, that equalized the rights

and the duties of grandparents and uncles with regard to the

children of brothers or children or vice versa. Remember that

in classical Latin the masculine nepos and the feminine nepis

indicated only the sons of the son or daughter and their

extension to the position of filius/filia fratis or sororis dates

to the imperial era.”

In order not to be confused we can always say the daughter

of my son (=mia nipote) or the daughter of my sister

(=mia nipote). English is much more specific in this regard.

Saturday, August 10, 2019

|

|

La parola “PIUMINO” ha varie traduzioni in inglese,

esaminiamole!

1. Il piumino è una trapunta imbottita: Mia nonna era famosa

per i suoi piumini, io ne ho uno sul mio letto, è magnifico.

2. Il piumino è un giubbotto imbottito: A San Francisco,

anche d’estate è necessario indossare un piumino, con la

nebbia fa un freddo infernale.

3. Il piumino è un piumaggio morbido: Io preferisco un

cuscino imbottito di piumino.

Ma esistono anche altri significati:

1. Il piumino è un tipo di proiettile: Stai attento, quel fucile

spara piumini.

2. Il piumino è un accessorio da toilette: Molti anni fa andava

di moda incipriarsi con un piumino.

3. Il piumino è un arnese per spolverare: Gli scaffali hanno

bisogno di una spolverata, usa il piumino.

The word PIUMINO has different translations into English;

let’s take a look at them.

1. “Il piumino” is a quilt, a comforter, or a duvet: My grandmother

was famous for her quilts, I have one of them on my bed; it’s

magnificent.

2. “Il piumino” is a down anorak or a quilted jacket: In San Francisco,

even during the summer a down jacket is necessary, with the fog it’s

beastly cold.

3. “Il piumino” is down: I prefer a down-filled pillow.

However, there are other meanings:

1. “Il piumino” is a type of projectile: Be careful, that rifle shoots darts.

2. “Il piumino” is an accessory for the toilette: Many years ago it was

fashionable to powder one’s nose with a powder puff.

“Il piumino” is a device to dust with: The bookcases need dusting, use

the feather duster.

Saturday, August 3, 2019

|

|

PILLOW = CUSCINO O GUANCIALE? PARTE I

C’è una differenza tra un cuscino e un guanciale, in inglese c’è solo una parola: pillow. Secondo il Vocabolario Treccani della Lingua Italiana ci sono due significati diversi, eccoli: Il cuscino viene dal latino medievale, coxinum, una derivazione di coxa “coscia”, quindi “cuscino per sedere”. È una specie di sacchetto di forma rettangolare, quadrata, oppure tonda, ovale, generalmente di tela e ricoperto di una federe, o per usi ornamentali, di stoffe pregiate o di pelle, imbottito di lana, piume, crine, gommapiuma, ecc. cuscino da letto, i cuscini del divano (non è rispettata dall’uso la distinzione etimologica tra il guanciale, [deriva dal termine tedesco wanga

o wanka per guancia] che è proprio fatto per appoggiarvi la guancia, e il cuscino, che più propriamente serve per rendere morbide seggiole e poltrona o si adopera come ornamento sopra divani e simili). Per esempio: appoggiare la testa sul cuscino; stare semidisteso sorretto da due cuscini, dormire tra due cuscini, anche in senso figurato (ma più comune, tra due guanciali).

Is there a difference between a cuscino and a guanciale, in English there is only one word: pillow. According to the Dictionary of the Italian Language published by Treccanithere are two different meanings, here they are:

The cuscino comes from Medieval Latin coxinum, a derivation of coxa, “thigh”,therefore a “pillow to sit on”. It is a type of sack of rectangular, square, round or oval shape, usually made of canvas and covered by a pillowcase; or for ornamental use,made of fine fabrics or leather, stuffed with wool, feathers, horsehair, foam rubber, etc. bed pillow, couch pillows (the etymological distinction of use is not respected regarding guanciale [it derives from the German “wanga” or “wanka” for cheek] which is specifically

designed to lay your cheek upon, as opposed to cuscino, which more specifically is used to make chairs and armchairs softer and is used as an

adornment on couches and the like). For example: lean your head on a pillow [cuscino]; partially lay down supported by two pillows [cuscini], sleep between two pillows [cuscini], even in a figurative sense (but more commonly between two pillows [guanciali].

Saturday, July 20, 2019

|

|

INTERVIEW = INTERVISTA O COLLOQUIO?

Troppo spesso negli Stati Uniti la parola “INTERVIEW” è tradotta come

“intervista” senza pensare che ci sia una scelta.

Di nuovo, cito la Treccani: <<UN’INTERVISTA è un colloquio che un

giornalista, un corrispondente di agenzia, un radiocronista o altra

persona appositamente incaricata ha con una personalità politica, con

rappresentanti del mondo della cultura, dell’arte, dello sport, ecc. o in

genere con persone legate a fatti di cronaca, per averne dichiarazioni,

opinioni, notizie su determinati argomenti (di solito proposti attraverso

una serie di quesiti), che sono pubblicate poi su un giornale o

trasmesse per radio o televisione.>>

UN COLLOQUIO è: <<uno scambio di parole tra due persone o più, di

solito su argomenti di qualche importanza, una conversazione,

dialogo, discussione, discorso.>> È uno scambio di idee e di opinioni su

questioni d’interesse comune. È anche un esame svolto sotto forma di

conversazione, a volte richiesto in alcune facoltà universitarie, o un

colloquio che si sostiene per ottenere un incarico o un impiego.

All too often in the United States the word “INTERVIEW” in translated

into Italian as “INTERVISTA” without taking into consideration that

there may be an alternative.

Again, I quote from the Treccani dictionary of the Italian language:

<<INTERVISTA, is a dialogue, a conversation that a journalist, a

correspondent from an agency, a radio reporter, or other individual

specifically appointed has with politicians, representatives of the

world of culture, art, sport, etc., or generally with individuals tied to

news reporting, in order to obtain declarations, opinions, information

on specific arguments (usually carried out through a series of

questions), that are published in newspapers or aired on the radio or

television.>>

“COLLOQUIO”: <<an exchange of words between two or more

individuals, usually on subjects of some importance, a conversation,

dialogue, discussion, discourse.>> It is an exchange of ideas and

opinions on matters of common interest. It can also be an exam

which takes places as a conversation, at times a requirement for

admission to certain university departments, or an interview held in

order to obtain an appointment or a job.

Saturday, July 13, 2019

|

|

COGLIAMO QUEST’OCCASIONE PER AUGURARE A TUTTI I NOSTRI

AMICI STATUNITENSI UN FELICE 4 LUGLIO, GIORNO

D’INDIPENDENZA.

NON DIMENTICHIAMO CHE IN ITALIA LA FESTA DELLA REPUBBLICA

SI FESTEGGIA IL 2 GIUGNO (data del referendum istituzionale del

1946).

TANTI

AUGURI

WE TAKE ADVANTAGE OF THIS OPPORTUNITY TO WISH ALL OF OUR

AMERICAN FRIENDS A HAPPY 4TH OF JULY, INDEPENDENCE DAY.

DON’T FORGET THAT IN ITALY THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE

REPUBLIC OF ITALY IS CELEBRATED ON JUNE 2ND (the date of the

referendum of 1946).

Saturday, July 6, 2019

|

|

LE DOPPIE—PARTE IV

Ho trovato un articolo eccellente sul sito dell’Enciclopedia dell’italiano

della Casa Editrice Treccani, scritto nel 2011 da Andrea Viviani. Vorrei

condividerlo con voi lettori in varie parti.

DOPPIE VOCALI (conclusione)

Possono darsi in italiano anche doppie vocali. ⟼ Sigle a parte, esse sono

rarissime in inizio parola e non con tutte le vocali: si hanno in sostanza

la sola esclamazione aah! Ooh!,l’aggettivo raro aaeliano e un nutrito

contingente in oo-, prefisso che in medicine e biologia significa

<<uovo>>: ooblasto, oociesci, ecc.; sono però com’è evidente, termini

tutti fuori dall’uso comune.

Meno rare le doppie vocali sono in fine di parola, e in particolare:

- Con oo si danno numerose parole dal suffisso –zoo <<animale,

vivente>>: protozoo, spermatozoo, lo stesso zoo e forestierismi

vari: tattoo, voodoo, (quando non adattato invudù), Waterloo, ecc.;

- Non si ha in uu a eccezione dell’interiezione buu, che esprime

disapprovazione, o l’ideofono fiuu (⟼ onomatopee e

fonosimbolismo), che riproduce il vento o sottolinea uno scampato

pericolo;

frequentissime, per un totale di diverse migliaio, sono invece le vocali

doppie all’interno di parola; per la sola a si danno nel variegatissimo

quadro forestierismi(afrikaans), composti (extraamniotico), nome propri

e derivati da (kierkegaardiano), toponimi derivati (maastrichtiano). Con

l’eccezione di uu presente solo in termini o locuzione d’origine latina

(continuum, vacuumterapia, in perpetuum), doppie vocali sono

rappresentate in tutte le categorie del nostro lessico, termini di più largo

uso inclusi: cooperativa, coonestare, coorte, ecc.

All’incontro di due vocali identiche che appartengono a parole diverse in

sequenza, cade quella finale della prima. È in principio alla base

dell’impiego dell’⟼apostrofo:quest’oggi, un’anatra.

Alcune parole prefissate danno luogo a doppia vocale: preesame,

antiilluministico. In questi casi, tra prefisso e parola si suole inserire un

⟼ trattino: pre-esame, anti-illuministico. Non si inserisce trattino, in

vece, nei ⟼ numerali ordinali composti col numero tre: ventitreesimo.

DOUBLE LETTERS—PART IV

I found an excellent article written by Andrea Viviani on the website of

the Publishing House Treccani for the Encyclopedia of Italian. I would

like to share it with you readers in various sections.

DOUBLE LETTERS—PART IV (conclusion)

I found an excellent article written by Andrea Viviani on the website of

the Publishing House Treccani for the Encyclopedia of Italian. I would

like to share it with you readers in various sections.

You can even find double vowels in Italian, putting aside acronyms, they

are extremely rare at the beginning of words and don’t apply to all

vowels: there are the exclamations aah! Ooh!,(no need to translate

here), the rare adjective aaeliano (I have no idea where they found this

one) and a temporary nutrition in oo-, a prefix that in medicine and

biology means <<egg>>: ooblasto, oociesci, etc. which are obviously

terms way outside of common usage.

Less rare among the double vowels are at the end of words, specifically:

- With oo there are many words with the suffix –zoo <<living animal>

>: protozoo, spermatozoo, along with the word zoo itself and

various foreign terms: tattoo, voodoo(when the latter isn’t found in

the form of vudù), Waterloo, etc.;

- The uu doesn’t exist except in the interjection buu, that expresses

disapproval, or the idiophone fiuu (onomatopoeia and phonic

symbolism), which copy the wind and underline a danger avoided;

very frequent, for a total of several thousands, are double vowels

found inside words, only for the letter a there is a large variety with

foreign derivations (Afrikaans), and compound words

(extraamniotico), proper nouns derived from (kierkegaardiano), and

place names derived from (maastrichtiano). With the exception of

uu found only in terms with Latin origins (continuum,

vacuumterapia, in perpetuum), double vowels are represented in all

of the categories of our lexicon. Terms of wide use include

cooperativa, coonestare, coorte, etc.

Where two identical vowels which belong to different words in sequence,

the later from the first word is dropped, this is the beginning of the use

of the apostrophe: quest’oggi, un’anatra. Certain words with prefixes use

double vowels: preesame, antiilluministico. In these instances it is

common to insert a hyphen: pre-esame, anti-illuministico. However, a

hyphen is not used in compound ordinal numbers with the number three:

ventitreesimo.

Saturday, June 29, 2019

|

|

LE DOPPIE—PARTE III

Ho trovato un articolo eccellente sul sito dell’Enciclopedia dell’italiano

della Casa Editrice Treccani, scritto nel 2011 da Andrea Viviani. Vorrei

condividerlo con voi lettori in varie parti.

DOPPIE VOCALI (parte III- introduzione)

Possono darsi in italiano anche doppie vocali. ⟼ Sigle a parte, esse

sono rarissime in inizio parola e non con tutte le vocali: si hanno in

sostanza la sola esclamazione aah! Ooh!,l’aggettivo raro aaeliano e

un nutrito contingente in oo-, prefisso che in medicine e biologia

significa <<uovo>>: ooblasto, oociesci, ecc.; sono però com’è

evidente, termini tutti fuori dall’uso comune.

Meno rare le doppie vocali sono in fine di parola, e in particolare:

- Inesistenti con aa, sono invece numerosissime le parole in ee,

per quando siano autoctoni i soli plurali delle parole in –ea

(cornea, marea) o –eo (spontaneo); la maggior parte è formata

da ⟼ grecismi (calchee, eraclee), ⟼ francesismi (tutti in accentati

sulla prima delle due vocali: matinée, tournée) e ⟼anglicismi

(duty free, frisbee); anche linea ha per derivato lineetta, da cui il

composto guardalinee;

- Con ii si hanno solo i plurali delle parole in –io -quando non ridotti,

nell’uso attuale, a una sola i (corridoi è preferito a corridoii,

monopoli a monopolii, ecc.), o scapati alla consuetudine, ormai

rara, dell’accento circonflesso (principî, o a quella, decisamente

desueta, della j: studj) – che abbiamo la i tonica: pii, zii, e dai

passati remoti di prima persona singolare dei verbi in –ire: dormii,

partii, ecc.;

[La conclusione continua la settimana prossima.]

DOUBLE LETTERS—PART III (introduction)

I found an excellent article written by Andrea Viviani on the website

of the Publishing House Treccani for the Encyclopedia of Italian. I

would like to share it with you readers in various sections.

You can even find double vowels in Italian (putting aside acronyms)

they are extremely rare at the beginning of words and don’t apply to

all vowels. There are the exclamations aah! ooh! (no need to

translate here), the rare adjective aaeliano (I have no idea where

they found this one) and a temporary nutrition in oo-, a prefix that in

medicine and biology means <<egg>>:ooblasto, oociesci, etc. which

are obviously terms way outside common usage.

Less rare among the double vowels are at the end of words,

specifically:

- Nonexistent with aa, the words in ee are very numerous in as

much as only the plurals are autochthon, for example: –ea

(cornea, marea) or –eo (spontaneo); most of these words have

Greek roots: (calchee, eraclee), French roots (all of the accents

are on the first of the two vowels: matinée, tournée) and English

roots (duty free, frisbee); evenlinea, has as a derivative lineetta,

and the compound word guardalinee;

- With the ii there are only the plurals of words ending in –io when

they haven’t been shortened in present-day usage to a single i

(corridoi is preferable to corridoii, monopolito monopolii, etc.),

or removed by now from the rare use of the circumflex accent

(principî, or the decidedly not used j: studj), we have the tonic i:

pii, zii, and in the first person singular of the past absolute tense

of 3rd category verbs ending in –ire: dormii, partii, etc.,

[The conclusion continues next week.]

Saturday, June 22, 2019

|

|

LE DOPPIE—PARTE II

Ho trovato un articolo eccellente sul sito dell’Enciclopedia dell’italiano

della Casa Editrice Treccani, scritto nel 2011 da Andrea Viviani.

Vorrei condividerlo con voi lettori in varie parti.

DIFFICOLTÀ E PROBLEMI

Le doppie suscitano problemi di ortografia a causa di

1. Pressioni dialettali: al Nord della Penisola, nella pronuncia la

tendenza generale è allo⟼ scempiamento, alla cancellazione cioè di

una delle doppie: a[fit]o per affitto; cava[let]o per cavalletto, ecc.; al

Centro-Sud, viceversa, è sistematica la pronuncia intensa di “b” e “g”

tra vocali; ta[bb]ella per tabella, cu[gg]ino per cugino, ecc.;

naturalmente questi fenomeni possono avere riflessi nella scrittura;

2.

Vicende etimologiche che perturbano la coerenza del sistema, in

particolare nel caso della “z” sia sorda sia sonora: sempre ‘intensa’

nella pronuncia standard di base toscana, nella grafia può occorrere

correttamente prima singola, poi doppia, poi ancora singola, perfino

all’interno della stessa parola: razionalizzazione.

DOUBLE LETTERS—PART II

I found an excellent article written by Andrea Viviani on the website

of the Publishing House Treccani for the Encyclopedia of Italian. I

would like to share it with you readers in various sections.

DIFFICULTIES AND PROBLEMS

Double letters cause spelling problems because of:

- Dialectal pressures: in the North of the Peninsula, the general

pronunciation is towards shortening, or the elimination of one of

the double letters: a[fit]o for affitto (rent); cava[let]o for

cavalletto (easel), etc.; in the Central and Southern parts of the

country, intense pronunciation is common of the letters “b” and

“g” between vowels: ta[bb]ellafor tabella (chart), cu[gg]ino for

cugino (cousin), etc.; naturally these characteristics can be

reflected in writing;

Etymological occurrences that disturb the coherence of the system,

particularly in the case of the “z”, both unvoiced and voiced: always

‘intense’ in the standard pronunciation of Tuscan, in writing it can

occur for the first time correctly as a single letter, then as a double,

and even inside the same word: razionalizzazione (rationalization).

Saturday, June 15, 2019

|

|

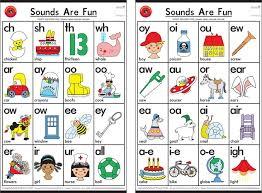

LE DOPPIE—PARTE I

Ho trovato un articolo eccellente sul sito dell’Enciclopedia dell’italiano

della Casa Editrice Treccani, scritto nel 2011 da Andrea Viviani.

Vorrei condividerlo con voi lettori in varie parti.

LA NATURA E LE RESTRIZIONI DELLE DOPPIE LETTERE:

In italiano diverse parole grafiche contengono lettere ripetute

tradizionalmente chiamate doppie (⟼le doppie, o le doppie lettere).

La ripetizione riguarda principalmente le consonanti. In particolare,

va osservato che:

1. Le doppie sono solo precedute e seguite da vocale: mai, quindi, in

inizio o fine di parola (fanno eccezione i forestierismi ormai in uso

comune: call, pull, lloyd, ecc.);

2. Hanno valore distintivo: esistono cioè coppie di parole che si

distinguono proprio per la presenza o assenza della doppia: pala ~

palla; caro ~ carro; copia ~ coppia; sete ` sette, ecc.

3. Graficamente sono possibili con tutte le consonanti tranne la “h”

e i digrammi e i trigrammi: <gn; gl(i), sc(i); e La “q” è doppia sono in

due parole: soqquadro e il tecnicismo musicale beqquadro (variante

di bequadro).

DOUBLE LETTERS—PART I

I found an excellent article written by Andrea Viviani on the website

of the Publishing House Treccani for the Encyclopedia of Italian. I

would like to share it with you readers in various sections.

THE NATURE AND RESTRICTIONS OF DOUBLE LETTERS:

In Italian, various graphic words contain letters that are repeated,

traditionally called doubles ( the doubles, or double letters). The

repetition mainly deals with consonants. In particular, it must be

noted that:

1. Doubles are preceded and followed by a vowel, never, therefore,

at the beginning or at the end of a word (the exceptions are

foreignism in common use: call, pull, lloyd, etc.);

2. They have a distinctive value: meaning that there exist pairs of

words that are distinguished precisely by the presence or absence

of a double letter: pala ~ palla [shove ~ ball]: caro ~ carro [dear ~

wagon]; copia ~ coppia [copy ~ couple]; sete ~ sette [thirst ~

seven]; etc.

3. Graphically speaking doubles are possible with all the cons

onants except the “h” and the digraphs and the trigraphs: <gn; gl(i)

, sc(i); and The “q” is doubled only in two words: soqquadro

[disorder/confusion] and the technical musical term beqquadro

[natural] (a variation of bequadro).

The “q” is doubled only in two words: soqquadro [disorder/confusion]

and the technical musical term beqquadro [natural] (a variation of

bequadro).

Saturday, June 8, 2019

|

|

La FESTA DELLA REPUBBLICA ITALIANA: Dopo la fine della

seconda guerra mondiale, l’Italia doveva scegliere se rimanere

monarchia costituzionale o diventare repubblica. Per la prima volta

le donne avevano il voto, e hanno votato! Erano circa 13 milioni di

donne e circa 12 milioni di uomini, l’equivalente all'89,08% degli

allora 28.005.449 aventi diritto al voto.

BUON 73° COMPLEANNO ITALIA!

FESTA DELLA REPUBBLICA ITALIANA: After the end of the Second

World War, Italy had to choose to remain a constitutional monarchy

or become a republic. For the first time women were given the vote,

and they voted! Approximately 13 million women and 12 million men

voted, the equivalent of 89.08% of the then 28,005,449 individuals

having the right to vote.

HAPPY 73RD BIRTHDAY ITALY! hell

Saturday,June 1, 2019

|

|

Secondo dei fatti ritrovati sul sito web di L'Organizzazione

delle Nazioni Unite per l'alimentazione e l'agricoltura, in

sigla FAO,

Sapete che:

1. L’Italia è il produttore maggiore di riso in Europa?

2. La Lombardia e il Piemonte sono considerati il bacino

del riso d’Italia?

3. La produzione di riso è incominciata verso la metà del

XV secolo?

4. Leonardo da Vince è riconosciuto per il suo contributo

della costruzione dei canali che drenano l’acquitrino della

pianura padana?

5. Camillo Cavour ha campionato la costruzione alla fine

del 19° secolo del canale che porta l’acqua dal Fiume Po e

Lago Maggiore per mantenere la produzione di riso e altri

prodotti agricoli a Vercelli-Alessandria, Pavia e Novara? Il

canale porta il suo nome.

According to statistics found on the website of the Food

and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, FAO

Did you know:

1. That Italy is the largest rice producer in Europe?

2. The regions of Lombardy and Piedmont are Italy's rice

bowl?

3. Rice production in Italy started around the middle of

the 15th Century?

4. Leonardo da Vinci is known for his contribution to the

building of channels to drain the marshlands of the Po

river plains?

5. Camillo Cavour championed the construction in the late

19th Century of a canal that brought water from the Po

River and Lake Maggiore to support the production of rice

and other crops in Vercelli-Alessandria, Pavia and Novara?

The canal is now called Cavour Canal.

Saturday, May 25, 2019

|

|

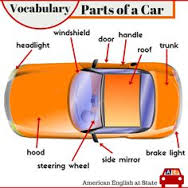

PARTS OF A CAR, PART II

This time I decided to provide you with automobile vocabulary

from English to Italian; it will make it easier when you purchase

your FIAT, Alfa Romeo, Maserati and/or Ferrari

|

| hatchback |

il portellone posteriore |

hazard/warning lights

|

il lampeggiatore d’emergenza |

| headlight |

il fanale anteriore |

| hood |

il cofano |

| ignition |

l’accensione |

| motor |

il motore |

| odometer |

il contachilometri |

| pedal |

il pedale |

| rear view mirror |

lo specchietto |

roof

|

il tetto |

seat

|

il sedile |

| seatbelt |

la cintura di sicurezza |

| side view mirror |

lo specchietto laterale |

| spare tire |

la ruota di scorta |

| speedometer |

il tachimetro |

| stearing wheel |

il volante |

tachometer

|

il contagiri |

| tire (informal) |

la gomma |

| tires |

i penumatici |

trunk

|

il bagagliaio |

windshield

|

il parabrezza |

| windshield wipers |

il tergicristallo |

|

|

Questa volta ho deciso di fornire una lista del lessico automobilistico

dall’inglese all’italiano; così l’acquisto della vostra FIAT, Alfa Romeo,

Maserati e/o Ferrari sarà più facile.

Saturday, May 18, 2019

|

|

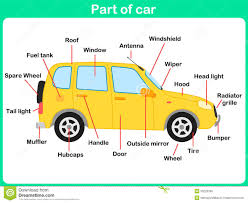

PARTS OF A CAR, PART I

This time I decided to provide you with automobile

vocabulary from English to Italian; it will make it

easier when you purchase your FIAT, Alfa Romeo,

Maserati and/or Ferrari.

| airbag |

l’airbag |

| backup light |

il proiettore di retromarcia |

| brake |

il freno |

| brake lever |

la leva del freno |

| brake lights |

le luci di stop |

| bucket seat |

il sedile anatomico |

| bumper/fender |

il paraurti |

| car door |

lo sportello |

| car horn |

il clacson |

| car keys |

le chiavi della macchina |

| chains |

le catene |

| clutch |

la frizione |

| cruse control |

il regolatore di velocità |

| dashboard |

il cruscotto |

| directional signal |

l’indicatore di direzione |

| door handel |

la maniglia |

| floor mat |

il tappetino |

| gas gauge |

l’indicatore della benzina |

| gas pedal/accelerator |

l’acceleratore (m) |

| gas tank |

il serbatoio della benzina |

| gear |

la marcia |

| gearshift |

la leva del cambio |

| glove box |

il cassetto portaoggett |

| GPS |

GPS |

Questa volta ho deciso di fornire una lista del lessico

automobilistico dall’inglese all’italiano; così l’acquisto

della vostra FIAT, Alfa Romeo, Maserati e/o Ferrari

sarà più facile.

Saturday, May 11, 2019

|

|

Che divertimento! Una lista di 18 parole italiane che contengono

tutte le vocali (NON RIPETUTE). Ce la fate a pronunciarle tutte?

| 1. Aiuole |

Flowebeds |

| 2. Aquilone |

Kite |

| 3. Aquilotte |

Little eagles |

| 4. Bruciapelo |

Point blank |

| 5. Crepuscolari |

Twilight/Hazey |

| 6. Documentari |

Documentaries |

| 7. Educatori |

Educators/Teachers |

| 8. Estuario |

Estuaries |

| 9. Funicolare |

Funicular/Cable railway |

| 10. Giuocare |

To play |

| 11. Maiuscole |

Uppercase/Capital letters |

| 12. Mutazione |

Mutation |

| 13. Persuasivo |

Persuasive |

| 14. Pneumatico |

Inflatable/Tire |

| 15. Profumeria |

Perfume shop |

| 16. Sciacquone |

Toilet flush |

| 17. Sequoia |

Sequoia/Redwood |

| 18. Umanesimo |

Humanism |

What fun! A list of 18 Italian words that contain all the vowels (not

repeated). Can you pronounce all of them?

|

|

GUARDIAMO IL TRAPASSATO REMOTO.

Il trapassato remoto è un tempo composto formato dal passato

remoto dell’ausiliare avere oessere + participio passato:

| Con avere: |

Io ebbi comprato |

Noi avemmo preso |

| |

Tu avesti finito |

Voi aveste dato |

| |

Lui/Lei ebbe scoperto |

Loro ebbero detto |

| Con essere: |

Io fui andata/o |

Noi fummo partite/i |

| |

Tu fosti uscita/o |

Voi foste sparite/i |

| |

Lei fu caduta |

Loro furono esiliate |

| |

Lui fu caduto |

Loro furono esiliati |

Il trapassato remoto descrive un’azione che ha luogo prima di

un’altra azione al passato remoto. È usato SOLO quando:

1. La frase principale è al passato remoto; e

2. Quando è introdotto da un avverbio di tempo: dopo che,

quando, (non) appena, finché.

Ecco alcuni esempi:

Dopo che il medico ebbe ingessato la gamba della bambina, lei si

sentì meglio.

Quando ebbero sentito l’allarme, i vigili del fuoco corsero

all’incendio.

Finché fummo contenti, restammo insieme.

LET’S LOOK AT THE PRETERITE PERFECT/PAST ANTERIOR

TENSE (TRAPASSATO REMOTO).

The preterite perfect is a compound tense formed by the past

absolute of the auxiliary verbsTo have (avere) or To be (essere)

+ past participle. [See above for these conjugations.]

The preterite perfect describes an action that takes place before

an action in the past absolute. It is used ONLY when:

1. The main phrase is in the past absolute; and

2. When it is introduced by an adverb of time: after, when, as

soon as, as long as.

Here are some examples:

After the doctor had put the girl’s leg in a plaster cast, she felt

better.

When they had heard the alarm, the firefighters ran to the blaze.

As long as we were happy, we stayed together.

|

|

Il giorno dopo Pasqua ha vari nomi: lunedì dell'Angelo, lunedì di

Pasqua, oppure Pasquetta. È una festa sia religiosa sia civile. Il

nome della festa religiosa deriva da Matteo 28 1-6, dove è

descritto il giorno in cui le donne andarono alla tomba di Gesù e

trovandola vuota ebbero paura, ma apparve un angelo che disse

loro di non temere perché Gesù era risorto.

Il giorno dopo la domenica di Pasqua però è anche una festa civile

che fu introdotta dallo Stato italiano dopo la Seconda Guerra

Mondiale per allungare la festa di Pasqua. Di solito, nonostante il

proverbio “Natale con i tuoi, Pasqua con chi vuoi,” il lunedì

dell’Angelo è spesso trascorso con parenti e amici in una

scampagnata, un pic-nic all’aperto, o se fa brutto tempo, in una

trattoria in campagna.

Da dove viene questa tradizione? Un’interpretazione ha radici

religiose. Si dice che è bello fare una passeggiata o una

scampagnata fuori le mura della propria città per ricordare

l’apparizione di Gesù ai discepoli diretti a piedi verso la cittadina di

Emmanus.

Qualunque siano le origini, è un giorno divertente e rilassante.

Perciò, BUON DIVERTIMENTO!

The day after Easter has several names: Monday of the Angel,

Easter Monday, or “Pasquetta” (literally, little Easter). It is both

a religious and lay holiday. The name for the religious holiday

comes from Matthew 28 1-6, where the day is described as the

one when the women went to Jesus’ tomb and finding it empty

they were afraid, but an angel appeared telling them not be

scared because Jesus had risen.

The day after Easter Sunday however is even a lay holiday that

was introduced by the Italian government after the Second World

War in order to lengthen Easter. Usually, notwithstanding the

proverb “Christmas with your family, Easter with whomever you

choose” Easter Monday is often spent with relatives and friends in

a “day trip to the country,” an open-air picnic, or if the weather is

bad, at a country restaurant.

Where does this tradition come from? One interpretation has

religious roots. It is said that it’s lovely to take a walk or to picnic

outside the city walls to remember the apparition of Jesus to the

disciples headed on foot the town of Emmanus.

Whatever the origins may be, it is a dun and relaxing day.

Therefore, ENJOY!

Saturday, April 20, 2019

|

|

I metalli (in ordine alfabetico) e le loro leghe più comuni

sono:

· L’acciaio (leghe ferro-carbonio-cromo-nichel ed altri

metalli)-Steel

· L'alluminio (Al)-Aluminum

· L'argento (Ag)-Silver

· Il bronzo (lega rame-stagno, ma anche -alluminio,

-nichel, -berillio)-Bronze

· Il ferro (Fe)-Iron

· Il mercurio (Hg)-Mercury

· L'oro (Au)-Gold

· L'ottone (lega rame-zinco, con aggiunta di Ferro,

Stagno, ed altri metalli)-Brass

· Il platino (Pt)-Platinum

· Il piombo (Pb)-Lead

· Il rame (Cu)-Copper

· Lo stagno (Sn)-Tin

· Il titanio (Ti)-Titanium

· Lo zinco (Zn)-Zinc

The most common metals (in alphabetical order) and

their alloys are:

· Aluminum-Alluminio

· Brass-Ottone (combines copper and zinc, with addition

of iron, tin, and other metals·)

· Bronze-Bronzo (combines copper and tin, but also with

aluminum, nickel, beryllium)

· Copper-Rame

· Iron-Ferro

· Gold-Oro

· Lead-Piombo

· Mercury-Mercurio

· Platinum-Platino

· Silver-argento

· Steel-acciaio (combines iron, carbon, chrome, nickel,

and other metals)

· Tin: stagno

· Titanium-Titanio

· Zinc-Zinco

Saturday, April 13, 2019

|

|

COSA SONO LE CONGIUNZIONI AVVERSATIVE?

Le congiunzioni avversative sono congiunzioni semplici,

che indicano un rapporto conflittuale tra due clausole

nella stessa frase. Questo rapporto può essere espresso

in modi diversi:

1. Un’azione si svolge nonostante esista un

impedimento. Per esempio: Ho già cenato, ma

volentieri prendo un bicchiere di vino con voi.

2. Si spiega come possa esistere un ostacolo. Per

esempio: È tardi, dovrei già essere a casa a letto, però

non me la sento.

3. Indica come si possa fare qualcosa di più. Per

esempio: Avevo intenzione di lavare dei panni a mano,

ma andrò in lavanderia e farò vari carichi di bucato.

4. La frase può riferirsi a un evento irrealizzabile.

Per esempio: Preferisco rimanere a casa sotto le

coperte piuttosto che uscire, fa freddo.

Ecco un elenco di congiunzioni avversative con le loro

traduzioni in inglese:

| Anzi |

actually, on the contrary |

| Bensì |

but rather |

| Comunque |

anyway |

| D’altra parte |

on the other hand |

| D’altro canto |

on the other hand |

| Eppure |

yes, but still |

| Invece |

but instead |

| Ma |

but however |

| Nondimeno |

never the less, regardless |

| Nonostante |

despite, although |

| Però |

but, however |

| Sebbene |

even though, albeit |

| Tuttavia |

nevertheless |

WHAT ARE ADVERSATIVE CONJUNCTIONS?

Adversative conjunctions are simple conjunctions that

refer to a conflict between two phrases in a sentence.

This relationship can be stated in different ways:

1. An action is carried out notwithstanding the

existence of an impediment. For example: I already

had dinner but I will gladly join you for a glass of wine.

2. It explains how an obstacle may already exist: For

example: It’s late, I should already be home in bed,

but I don’t feel like it.

3. Indicates how an additional task can be carried out.

For example: I was planning on doing some laundry by

hand, however, I’ll go to the laundromat and do

several big loads.

4. The sentence could indicate an event that cannot

take place. For example: I prefer to stay home in bed

under the covers rather than go out. It’s cold.

For a list of adversative conjunctions, see above.

Saturday, April 6, 2019

|

|

In Italia si dice Pesce d’aprile, negli Stati Uniti si

celebra il 1° aprile con “April Fool’s”. Controllate i miei

blog del 2016 e del 2017 per le origini di questa festa e

alcune espressioni italiane che hanno a che fare con i

pesci. Oggi invece, ho scelto di darvi una lista parziale

del vocabolario peschereccio. È perfetta per il 1° aprile.

BuonPESCE D’APRILE e BUON APPETITO!

- Alici = anchovies

- Anguilla = eel

- Busbana = Norwegian pout

- Calamaro = squid

- Canocchia = mantis shrimp

- Capasanta = scallop

- Cefalo = mullet

- Cernia = grouper

- Cozza = mussel

- Dentice = snapper

- Gambero = crayfish, shrimp, prawn

- Granchio = crab

- Lampuga = dolphinfish

- Merluzzo = cod

- Nasello = hake

- Occhiata = sea bream

- Pagello = Pandora, sea bream

- Palamita = bonito