|

|

|

|

|

|

Ho trovato questo bellissimo augurio natalizio e vorrei

condividerlo:

I found this lovely christmas wish and I would like to share it with you:

To who loves to sleep but wakes up always in a good mood; to who

still greets other with a kiss; to who works much but enjoys even

more; to who is in a hurry but doesn’t tap the car horn at traffic lights;

to who arrives late but doesn’t look for excuses; to who turns off the

television in order to chat; to who is twice as happy when dividing in

half; to who rises early to help a friend; to who has the enthusiasm of

a child but the thoughts of and adult; to who sees black only when it is

dark; to who doesn’t wait for Christmas to be better

Buon Natale a tutti -- Merry Christmas to all

Saturday, December 25, 2021

|

|

Anche dopo molto tempo, trovo che ci sono delle parole che i miei studenti

continuano a confondere.

= =  ?? ??

1. Un luogo dove ci sono animali e coltivazione agricola è una FATTORIA, non

una FABBRICA. Una fabbrica costruisce prodotti.

Esempi: Oggigiorno molte fattorie in California hanno dovuto cambiare la loro

produzione di uva e mandorle perché manca l’acqua.

La fabbrica FIAT fu fondata l’11 luglio 1899 da Giovanni Agnelli; le lettere sono

l’acronimo di Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino.

2. È un COLLOQUIO di lavoro; un’INTERVISTA è fatta da una giornalista.

Esempi: Il capo dell’azienda ha sottoposto a colloquio i due candidati finalisti

per il posto di caporeparto. L’intervista con il Presidente del Consiglio è durata

quarantacinque minuti.

3. Si dice FONDAMENTALMENTE, IN PRATICA; in italiano non esiste la parola

“basicamente”.

Esempi: In pratica, se volete viaggiare all’estero questi giorni, in oltre al

passaporto valido, è necessario un vaccino e un tampone per accertarsi di non

avere COVID.

Questa ricetta è facilissima, ci sono fondamentalmente tre ingredienti: farina,

acqua e uova.

Even after all this time, I find there are several words that confuse my

students.

1. A FARM is a “fattoria” not a “fabbrica”; the latter is a FACTORY.

For example: Today many farms [fattorie] in California have had to change

their production of grapes and almonds due to lack of water.

The FIAT factory [fabbrica] was established July 11, 1899 by Giovanni Agnelli;

the letters are the acronym for Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino. [in order:

Factory Italian Automobile Turin].

2. A work INTERVIEW is “colloquio”; an interview on television or in the

newspapers is “intervista”.

For example: The head of the company interviewed the two finalists for the

position of manager.

The interview with the Prime Minister lasted forty-five minutes.

3. The translation of BASICALLY into Italian is “fundamentally” or “in practice”,

the word “basicamente”, although sounding close, doesn’t exist.

For example: Basically, if you want to travel abroad these days, in addition to

your passport, you will need a vaccination and a negative COVID test. This

recipe is very easy there are three basic ingredients: flour, water and eggs.

Saturday, December 18, 2021

|

|

| |

ATTITUDINE-ATTEGGIAMENTO = ATTITUDE?

Come si traduce la parola inglese “attitude” in italiano? NON è attitudine ma

comportamento. Attitudine è la predisposizione verso particolari attività (in

inglese si dice “aptitude”.) Abbiamo davanti un altro falso amico:

Secondo il dizionario Hoepli online di La Repubblica,

ATTITUDINE:

1. è la “Disposizione naturale, inclinazione per una determinata attività:

avere attitudine al disegno, per lo studio; non avere particolari attitudini;

avere attitudine a fare un lavoro. Sinonimi: propensione, idoneità.

2. è l’atto, l’atteggiamento, la posizione del corpo: un fedele in attitudine di

preghiera

Mentre:

ATTEGGIAMENTO è:

1. il modo di atteggiare il corpo o parti di esso; atto, gesto: l’atteggiamento

da oratore, mettersi in atteggiamento minaccioso. Sinonimo: posa.

2. Contegno, comportamento: atteggiamento sdegnoso, atteggiamento di

prima donna, atteggiamento antipatico.

3. Valutazione critica, posizione ideologica nei confronti di un problema, di

una teoria e simili: l’atteggiamento dell’opposizione verso la politica di

governo.

How do we translate the English “attitude” into Italian? It ISN’T “attitudine”

but “comportamento”. “Attitudine” is the predisposition towards a particular

activity, “aptitude” in English. We are facing another false friend.

According to the online dictionary Hoepli of the publication La Rebubblica,

ATTITUDINE:

1. Is the natural disposition, inclination towards a specific activity: have the

aptitude for drawing, for study, not having a particular aptitude towards a

specific type of work. Synonyms: propensity, suitability.

2. Is the act, positioning of the body: a worshiper in the position of prayer.

ATTEGGIAMENTO is:

1. The way to position one’s body or parts thereof; an act, a gesture: the

manner of an orator, assume a threatening position. Synonym: pose.

2. Comportment: a haughty behavior, to act like a prima donna, rude,

unpleasant behavior.

3. Critical evaluation, an ideological position regarding a problem a theory,

etc.: the position of the opposition towards the politics of the government.

Saturday, December 11, 2021

|

|

| |

EGG—Part 3

Robin egg blue - Wikipedia In addition to the ability to order breakfast in Italy,

there are many other useful expressions we can explore:

1. Eggnog

2. Egg roll (Chinese food)

3. A good egg (describing a kind, nice person)

4. Goose egg (on a scoreboard)

5. Have egg on your face (figurative: to be embarrassed)

6. Nest egg

7. Robin’s-egg blue (a turquoise color)—the literal translation of the Italian is

sugar-paper blue 8. A bad egg (describing a mean, dishonest person) —the

literal translation of the Italian is a rotten apple.

UOVO—Parte 3 UOVO—Parte 3

In oltre all’abilità di ordinare la prima colazione in Italia, ci sono molte altre

espressioni utili che possiamo esplorare:

1. Zabaione

2. Involtino primavera (cibo cinese)

3. Una brava persona (letteralmente: un buon uovo)

4. Zero spaccato (su un tabellone segnapunti)

5. Avere il viso tutto rosso, essere imbarazzato (letteralmente: aver uovo

sulla faccia) sulla faccia)

6. Gruzzolo, risparmi (letteralmente: un nido)

7. Blu carta da zucchero (letteralmente: il blu dell’uovo di un pettirosso)

8. Mela marcia (letteralmente: un uovo cattivo)

Saturday, November 13, 2021

|

|

UOVO—Parte 2

Avete deciso di ordinare una colazione all’americana in Italia

ma non sapete come farlo. Abbiamo già visto che si dice “un

uovo” o “due uova”. Allora, come le volete, queste uova?

1. Un uovo fritto o uovo al tegamino

2. Un uovo sodo

3. Un uovo sott’aceto (un po’ strano di mattina, ma tutti i gusti

sono gusti) sono gusti)

4. Un uovo alla scozzese (Uovo bollito con salsiccia)

5. Uova strapazzate (di solito al plurale)

6. Un uovo alla coque

7. Un uovo nel cestino (uovo fritto in una fetta di pane)

8. Una frittata.

Buona colazione!

EGG—Part 2

You have decided to order an American-style breakfast in Italy,

however you don’t know how to do it. We have already seen

that we say one egg (“un uovo”) which is masculine singular or

two eggs (“due uova”) which is feminine. What would you like?

1. Fried egg

2. Hard-boiled egg

3. Pickled egg (a little odd in the morning, but there is no

accounting for taste) accounting for taste)

4. Scotch egg (boiled egg in sausage meat)

5. Scrambled eggs (usually used in plural form)

6. Soft-boiled egg

7. Egg-in-the-basket, aka toad-in-the-hole (an egg fried in a

slice of bread) slice of bread)

8. An omelet

Enjoy your breakfast!

Saturday, November 6, 2021

|

|

UOVO, Parte 1

Avete deciso di ordinare una colazione all’americana ma non

sapete come farlo. Prima di tutto, si dice “un uovo” e “due

uova”; il singolare è maschile, il plurale è femminile, PERCHÉ?

In generale, i sostantivi maschili che al singolare terminato in

“o”, al plurale si trasformano in “i” finale; uovo, in questo caso

fa eccezione. (Non è l'unico caso in cui si ha il singolare al

maschile e il plurale al femminile, ad esempio: braccio-braccia;

dito-dita; membro-membra; osso-ossa; riso-risa; ecc.) In

inglese è molto più facile, si aggiunge semplicemente una “s”

alla fine della parola al singolare.

Il plurale irregolare di questa parola è dovuto alla sua

etimologia latina: "uovo" deriva dal latino ovum, una parola

neutra. La regola latina afferma che le parole neutre, che al

singolare terminano in -um (nel nostro caso ovum), al plurale

finiscono in -a (ova). Il risultato è che se in latino queste

parole terminavano in "-a", la loro desinenza plurale neutra,

ora, in italiano, terminano in "-a" per affinità con il genere

femminile (siccome in italiano non esiste il neutro).

EGG—Part 1

You have decided to order an American-style breakfast in Italy,

however you don’t know which gender to use when you are

choosing between one egg (“un uovo”) which is masculine

singular and two eggs (“due uova”) which is feminine.

Usually, masculine nouns that end in “o” in the singular change

the final letter to “I” in the plural; “uovo” is an exception to

this rule. (It isn’t the only case in which the singular form is

masculine and the plural is feminine; for example:

braccio-braccia; dito-dita; membro-membra; osso-ossa;

riso-risa; arm-arms; finger-fingers; member-members;

bone-bones, laugh-laughs, etc.) In English, it is so much

easier; simply add an “s” to the end of the singular noun.

The irregular plural of this word derives from its Latin

etymology: “uovo” comes from the Latin ovum, a neutral noun.

The Latin rule states that neutral words, where the singular

ending is -um (as in our case ovum); in the plural they end in

-a (ova). Thus, if these words end in “a” in Latin, the plural

neutral, now, in order to maintain their affinity to the feminine,

in Italian they also end in “a” (since, in Italian there is no

neutral).

Saturday, October 30, 2021

|

|

PREPOSIZIONI CON I MEZZI DI TRASPORTO: Parte 3

Fin ora abbiamo imparato che le due preposizioni più usate

sono “in” e “con”. (Vi prego di rivolgervi a Parte 1 di questo

tema.) In oltre, in Parte 2 abbiamo notato le eccezioni alla

regola dell’uso delle preposizioni “in” e “con”. In fine, ade

sso

esaminiamo due verbi, SALIRE e SCENDERE i quali usano

preposizioni diverse:

SALIRE SU + ARTICOLO

Per esempio:

1. Gli sposi sono saliti sulla carrozzella per un giro

romantico della città. romantico della città.

2. È meglio salire sull’autobus al capolinea se vuoi un

posto. posto.

SCENDERE DA + ARTICOLO

Per esempio:

1. Molti immigranti italiani agli Stati Uniti sono scesi

dalla nave all’Isola di Ellis a New York. dalla nave all’Isola di Ellis a New York.

2. Marcellino è dovuto scendere dall’autobus perché si

comportava male. comportava male.

E rieccoci: Ancora un’altra ECCEZIONE:

1. Salire in macchina / entrare in macchina

2. Scendere dalla macchina / uscire dalla macchina

PREPOSITIONS WITH MEANS OF TRANSPORTATION: Part 3

Up to now, we have learned that the two most frequently used

prepositions are “in” and “con”. (Please refer to Part 1 of this

subject.) Additionally, in Part 2 we observed the exceptions to

the rule of the use of the prepositions “in” and “con”. Finally,

let us look at two verbs, SALIRE and SCENDERE that use

different prepositions.

SALIRE SU + ARTICLE [climb/get in-on]

For example:

1. The married couple got in the carriage for a

romantic tour of the city. romantic tour of the city.

2. It is better to get on the bus at the first stop if

you want a seat. you want a seat.

SCENDERE DA + ARTICLE [get off/disembark]

For example:

1. Many Italian immigrants to the United States

disembarked at Ellis Island in New York. disembarked at Ellis Island in New York.

2. Marcellino had to get off the bus because he was

misbehaving. misbehaving.

Here we go again: Another EXCEPTION:

1. Climb in [the] car/enter in [the] car

2. Descend from the car/get out of the car

Saturday, October 23, 2021

|

|

PREPOSIZIONI CON I MEZZI DI TRASPORTO: Parte 2

Eccezione alla regola dell’uso delle preposizioni “in” e “con”

con i mezzi di trasporto. [Vi prego di rivolgetevi alla Parte 1 di

questo tema, se volete ripassare le regole di base.]

Ci vuole la preposizione “a” quando ci si sposta a piedi o a

cavallo. Per esempio:

- È sempre una buona idea andare a piedi quando si può, fa

bene alla salute.

- Una delle unità della polizia a Roma pattuglia i giardini

Borghesi a cavallo

Ma attenti: Sì c’è anche l’espressione “in piedi” che significa

non essere seduti.

Per esempio:

- Una cena in piedi è la soluzione ideale per chi ha molti

amici e una casa piccola.

- L’autobus era pieno di gente e sono dovuta rimanere in

piedi per quasi tutto il tragitto

- In alcuni uffici, è la nuova moda lavorare in piedi.

PREPOSITIONS WITH MEANS OF TRANSPORTATION: Part 2

Exception to the rule of the use of the prepositions “in” and,

less often, “con” with means of transportation. [Please refer

to Part 1 of this subject, if you would like to review the basic

rules.]

We need to use the preposition “a” when we travel by/on foot

or by/on a horse.

For example:

1. It is always a good idea to go by/on foot when one can; it is

good for your health.

2. One of the branches of the police in Rome patrols the

Borghese Gardens on horseback.

Be careful however: Yes, the expression “in piedi” exists; it

means to stand; not seated.

For example:

1. A dinner served/consumed while standing is the ideal

solution for someone who has many friends and a small house.

2. The bus was full of people, so I had to stay standing for

nearly the entire trip.

3. In some offices, the new trend is to work standing up.

Saturday, October 16, 2021

|

|

PREPOSIZIONI CON I MEZZI DI TRASPORTO: Parte 1

Quali preposizioni usiamo con i mezzi di trasporto?

Di solito: “in” e, meno spesso, “con”.

La preposizione “in” si usa senza l’articolo e solo al singolare.

Ecco alcuni esempi:

1. Questa settimana andiamo in macchina fino a Los Angeles.

2. Ci piace viaggiare in treno perché possiamo rilassarci e

guardare il panorama.

3. Ma a volte, se dobbiamo attraversare lo stato, è più

conveniente andare in aereo.

4. Quando erano giovani, i miei genitori hanno attraversato

l’Atlantico in nave.

5. Mio nipote è veramente in forma, ogni giorno fa 50

chilometri in bicicletta

La preposizione “con” si usa sempre con l’articolo e sia al

singolare sia al plurale.

Ecco alcuni esempi:

- Ieri sono andata a scuola con la macchina di mio padre.

- Senti Mario, se viaggi con il treno da Roma a Milano fai prima.

- Da piccola, ho volato da Parigi a New York con un aereo ad

elica.

- Non mi piace viaggiare con i traghetti, soffro il mal di mare.

- A volte, i miei amici fanno un giro in Italia con la bici.

PREPOSITIONS WITH MEANS OF TRANSPORTATION: Part 1

Which prepositions do we use with means of transportation in

Italian?

Usually: “in” and, less often, “con” [in English we use “by’].

The preposition “in” is used without an article and only in front of

singular nouns.

Here are some examples:

- This week we will go to Los Angeles in a [by] car.

- We like to travel in a [by] train because we can relax and

look at the scenery.

- At times, however, if we have to cross the state, it is more

convenient to go in a [by] plane.

- When they were young, my parents crossed the Atlantic in a

[by] ship.

- My nephew is really in shape, every day he rides 30 miles in

a [by] bicycle.

The preposition “con” is always used with an article and the

nouns that follow it can be either in the singular or in the plural.

Here are some examples:

- Yesterday I went to school with [in] my father’s car.

- Listen Mario, if you travel with [by] train from Rome to Milan

it will be faster.

- When I was a little girl, I flew from Paris to New York with

[in] a prop plane.

- I don’t like to travel with [in/on] ferryboats, I get seasick.

At times, my friends take a tour of Italy with a [by] bike.

Saturday, October 9, 2021

|

|

| |

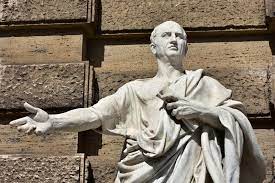

CICERONE/CICERO

Perché usiamo la parola “Cicerone” quando parliamo di una guida?

Per la risposta mi sono rivolta al Dizionario dei Modi di Dire

- Corriere della Sera (Hoepli Editore).

FARE DA CICERONE: Illustrare ad altri quello che si sa su un dato

argomento, e più specificamente fare da guida in un museo, in una città

o una zona d'interesse turistico, artistico o simili.

Il motivo per cui è stato scelto il nome di Cicerone può esser

nato dal paragone fra la sua eloquenza e la verbosità spesso comune

alle guide turistiche specializzate. Tuttavia nelle sue Lettere Cicerone

descrive con grande efficacia e diligenza la Grecia e le residenze dei

suoi grandi uomini, tanto che nel 1855 Jacob Burckhardt pubblicò un

volume intitolato “Il Cicerone, guida al godimento delle opere d'arte

italiane”, considerato un fondamentale repertorio storico e critico dei

nostri monumenti artistici.

FARE IL CICERONE: Fare sfoggio di molte conoscenze in modo

ampolloso e saccente; atteggiarsi a esperti di tutto; pretendere di

entrare nel merito di qualsiasi argomento anche parlando a sproposito.

Why do we use the word “Cicero” (Cicerone) when we are talking about

a guide? For the answer, I turned to The Dictionary of Common

Expressions of (the newspaper) Corriere della Sera (Hoepli Editore).

FARE DA CICERONE: To describe to others what one knows on a

particular topic, more specifically to be a guide in a museum, a city, or

an area of tourist, artistic, or other similar interests.

The reason why the name Cicero (Cicerone) was chosen may

have come from the comparison between his eloquence and the

wordiness of specialized tourist guides. Nevertheless, in his Letters,

Cicero describes, with great efficacy and diligence, Greece and the

homes of its great men, so much so that in 1855 Jacob Burckhardt

published a book titled “Cicero, guide to the enjoyment of Italian works

of art”, considered a fundamental historical and critical catalogue of our

artistic monuments.

FARE IL CICERONE: Show off one’s vast knowledge in a pompous and

arrogant manner; to act as an expert in everything; to insert oneself

into any topic even speaking inappropriately.

Saturday, October 2, 2021

|

|

POWER—Parte 4

Come abbiamo già visto, ci sono diversi modi di tradurre la parola inglese

“power” in italiano. I termini più comuni sono: forza, potenza e potere;

oggi tocca a potere!

Vi inoltro—con riconoscenza—queste osservazioni che provengono

dall’articolo: Forza, potenza e potere di A. Bertirotti e V. Succi -

marzo 2012 Riflessioni.it

Potere significa:

. Avere la capacità, la possibilità, il permesso, il diritto di fare qualche

cosa; cosa;

. Essere lecito o consentito;

. Essere possibile o probabile;

. Esprime un desiderio o un dubbio;

. Essere efficace, avere forza;

. Facoltà concreta di fare o non fare qualche cosa;

. Capacità di influire su persone;

. Funzione affidata per legge al titolare di una carica;

. Balia, dominio esercitato sugli altri;

. Esercizio dell’autorità in un determinato campo;

. La suprema autorità politica dello Stato;

. Proprietà di un corpo o sistema di produrre determinati fenomeni.

As we have already said, there are various ways to translate the English

word “power” into Italian. The most common forms are “forza”,

“potenza” and “potere”; today it is the turn of “potere”.

I am forwarding these findings—with my thanks—from the article: Forza,

potenza e potere di A. Bertirotti e V. Succi - marzo 2012 Riflessioni.it

POTERE means:

. To have the capacity, the possibility, the permission, the right to

do something; do something;

. To be lawful or permitted;

. To be possible or probable;

. It expresses a desire or a doubt;

. To be effective, to have strength;

. The concrete ability to do or not do something;

. The ability to influence other;

. The function given by law to an appointed official;

. The power or control over others;

. The exercise of authority in a specific field;

. The supreme political authority of the Government;

. The ability of a body or system to produce specified phenomena.

Saturday, September 25, 2021

|

| |

|

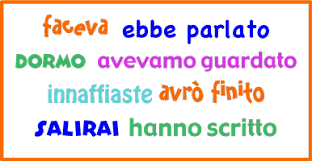

L’USO DEGLI ACCENTI—il circonflesso—

Parte III

Come mai troviamo l’accento circonflesso in francese e non in italiano?

Troviamo una risposta nel Corriere della Sera:

·Due parole possiamo spenderle anche per quel particolare accento che

ha la strana forma di una v rovesciata (ˆ) e che va sempre più

scomparendo dall’uso: il circonflesso. Si incontra ancora, ma anche qui

di rado, nella poesia, per indicare una sincope, cioè la soppressione di

una sillaba nel corpo di una parola: côrre per cogliere, tôrre per togliere,

fêro per fecero, tôsco per tossico, e così via; o anche per indicare

un’apòcope, cioè la soppressione di una sillaba in fine di parola: fûro per

furono, amâro per amarono, perdêro per perderono ecc. Ma quale poeta

di oggi pensa più di usare un côrre, un fûro e un perdêro? E se anche li

usasse, preferirebbe forse ricorrere anche qui ai due soliti accenti acuto

e grave, secondo la pronunzia: féro, perdéro, còrre, tòsco.

· Il circonflesso resiste invece di più per indicare la contrazione in una

delle due i nel plurale dei nomi in -io con la “i” atona (non accentata):

varî invece di varii, studî invece di studii, armadî invece di armadii. Ma

anche in questo caso il circonflesso appare inutile, bastando una

semplice i quando non sia possibile una confusione di senso: vari, studi,

armadi. Nei casi di senso incerto, molti preferiscono, anziché il

circonflesso, la doppia i: assassinii, plurale di assassinio, ma assassini

plurale di assassino, ammalii (verbo ammaliare), ma ammali (verbo

ammalare).

THE USE OF ACCENTS—circumflex accent—

Parte III

Why do we find the circumflex accent in French and not in Italian? We

find an answer in the newspaper Corriere della Sera.

· We can dedicate a few words to that particular accent that has the

odd shape of an upside-down v (^) and which is ever more rapidly

vanishing from use: the circumflex. It can still be found, and even here

less frequently, in poetry to indicate syncope, the elimination of a

syllable from the body of a word: côrre instead of cogliere [to

pick/gather], tôrre instead of togliere [to remove], fêro instead of

fecero [they did], tôsco instead of tossico [poisonous/toxic], and so

forth; or even to indicate an apocope, that is the elimination of a

syllable at the end of a word: fûro instead of furono [they were], amâro

instead of amarono [they loved], perdêro instead of perderono [they

lost], etc. Yet which poet today would think of using côrre, fûro and

perdêro? And even if she were to use one of these words, perhaps it

would be preferable to use one of the usual acute or grave accents,

depending on the pronunciation: féro, perdéro, còrre, tòsco. ·

· The circumflex hangs on instead to indicate the contraction of one of

the two “i” in the plural of words that end in -io where the i is

unstressed: varî instead of varii

[various], studî instead of studii [studies], armadî instead of armadii

[closets]. In the case where the meaning is uncertain, many prefer

instead of the circumflex accent, to use the double i: assassinii, plural

of assassinio [murder—the crime], but assassini plural of assassin

[murderer—the criminal], ammalii (verb ammaliare [to bewitch]), but

ammali (verb ammalare [to fall ill]).

Saturday, September 18, 2021

|

|

| |

L’USO DEGLI ACCENTI—Parte II (all’interno di una parola)

L’accento sulle vocali “e” e “o” all’interno di una parola è importante nei

vocabolari perché indica se la vocale accentata è aperta (è; ò) o chiusa

(é; ó), e perciò sappiamo come pronunciarla; per esempio: sorèlla e péso;

pòvero e órso.

Al di fuori dei vocabolari, si può inserire l’accento tonico all’interno nel caso

di omografi, cioè parole che sono uguali esclusivamente sul piano della

scrittura, ma la loro pronuncia e il loro significato variano. Per esempio:

desìderi (presente indicativo di desiderare) desidèri (sostantivo)

lègge (presente indicativo di leggere) légge (sostantivo)

pàgano (presente indicativo di pagare) pagàno (sostantivo o aggettivo)

scrìvano (congiuntivo di scrivere) scrivàno (sostantivo)

vìola (presente indicativo di violare) viòla (sostantivo)

THE USE OF ACCENTS—Part II (within a word)

The accent on the vowels “e” and “o” within a word is important in

dictionaries because it states if the pronunciation of the accented vowel is

open (è; ò) or closed (é; ó); thus we know how to pronounce it. For example:

sorèlla e péso; pòvero e órso = sister and weight; poor and bear.

In addition to dictionaries, we can insert a stress or emphatic accent in the

case of homographs, words whose similarity is only in how they are written,

their pronunciation and meaning are different. For example:

desìderi (present indicative of the verb to desire) desidèri (noun: desires)

lègge (present indicative of the verb to read) légge (noun: law)

pàgano (present indicative of the verb to pay) pagàno (noun and adjective: pagan)

scrìvano (present subjucnctive of the verb to write) scrivàno (noun: scribe)

vìola (present indicative of the verb to violate) viòla (noun: viola, violet, pansy)

Saturday, September 11, 2021

|

|

FARE-Parte 2

Come abbiamo visto la volta scorsa, il verbo FARE non ha un solo significato, ma

ha anche degli usi idiomatici particolari che sono più difficili da tradurre.

Sorridiamo un po’: se uno studente di madrelingua inglese prova a tradurre

letteralmente alcune espressioni come “fare i biglietti”, “fare benzina” o “fare lo

sci”, si trova in una cartiera, in un pozzo petrolifero o in una fabbrica di articoli

sportivi. Però, lo stesso vale se traduciamo dall’inglese all’italiano.

Consideriamo questi esempi:

As we saw last time, the verb FARE, does not only have one meaning; it also has

specific idiomatic uses that are more difficult to translate.

Let’s smile a little: if a native speaker of English tries to translate some of these

expressions literally, for example “make a ticket”, “make gasoline” or “make a

ski”, she may find herself in a paper mill, an oil well or a sporting goods factory.

However, the same holds true if we translate from English into Italian.

Let’s consider these examples:

| make a case |

perorare la causa di |

non fare un astuccio |

| make a killing |

guadagnare un sacco |

non fare un assassinio |

| make book |

scommettere |

non fare un libro |

| make an opening |

inaugurare |

non fare una breccia |

| make hay |

sfruttare a proprio vantaggio |

non fare fieno |

| make port |

raggiungere il porto |

non fare del vino dolce |

Saturday, September 4, 2021

|

|

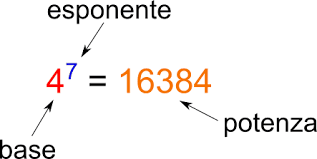

POWER—Parte 3

Come abbiamo già visto, ci sono diversi modi di tradurre la parola inglese

“power” in italiano. I termini più comuni sono: forza, potenza e potere. Li

esamineremo, uno alla volta; oggi tocca a potenza!

Vi inoltro—con riconoscenza—queste osservazioni che provengono dall’articolo:

Forza, potenza e potere di A. Bertirotti e V. Succi - marzo 2012 Riflessioni.it

Il termine potenza significa:

. Potere o forte influenza, specialmente a livello politico ed economico;

. Vigore, grande forza fisica;

. Intensità di un fenomeno;

. Violenza, vigore di un impatto;

. Proprietà di fornire determinate prestazioni o certi effetti;

. Nazione che svolge un ruolo determinante a livello nazionale;

. Industria che ha un ruolo preminente in un settore;

. Lavoro compiuto nell’unità di tempo da una macchina;

. Il numero che si ottiene moltiplicando la base per se stessa per il numero di

volte indicato dall'esponente. volte indicato dall'esponente.

As we have already said, there are various ways to translate the English word

“power” into Italian. The most common forms are “forza”, “potenza” and

“potere”. We will review them one at a time; today it is the turn of “potenza”.

I am forwarding these findings—with my thanks—from the article: Forza, potenza

e potere di A. Bertirotti e V. Succi - marzo 2012 Riflessioni.it

POTENZA means:

· Power or strong influence, especially at the political and economic levels;

· Vigor, great physical strength;

· The intensity of a phenomenon;

· Violence, the strength of an impact;

· The capability to provide specific features or certain effects;

· A nation that performs a specific function at the national level;

· An industry that predominates in a sector;

· Work carried out by a machine in a specified time period;

. The number that results from multiplying its base by itself, times the

number of the exponent—“to the power of”. number of the exponent—“to the power of”.

Saturday, August 28, 2021

|

|

L’USO DEGLI ACCENTI—Parte I (al termine di una parola)

In generale, le vocali a, i, o, u, alla fine di una parola, usano l’accento grave, per

esempio: università e là, mercoledì e lì, però e laverò, tribù e gioventù.

La vocale e alla fine di una parola usa l’accento grave quando ha una pronuncia

aperta, per esempio:

1. È (terza persona singolare del verbo essere);

2. Nei nomi propri: Giosuè, Mosè;

3. Nei nomi di origine straniera: caffè, tè.

La vocale e alla fine di una parola usa l’accento acuto quando ha una pronuncia

chiusa, per esempio:

1. Nelle parole composte di che: benché, perché, purché;

2. Nelle parole composte di tre: ventitré…ottantatré;

3. Nei monosillabi: sé, né;

4. Nelle terminazioni del passato remoto: dové, poté.

THE USE OF ACCENTS—Part I (at the end of a word)

Generally, the vowels a, i, o, u, at the end of a word use the grave accent (`),

for example: university and there, Wednesday and there, but and I will work,

tribe and youth.

The vowel e at the end of a word uses the grave accent (`) when its

pronunciation is open, for example:

1. È the third person singular of the verb “to be”;

2. With proper names: Joshua, Moses;

3. Nouns with non-Italian origins: coffee, tea.

The vowel e at the end of a word uses the acute accent (´) when its

pronunciation is closed, for example:

1. With words containing the word “che”: although, because, provided that;

2. With words containing the number three: twenty-three…eighty-three;

3. With monosyllabic words: him/herself, neither/nor;

4. At the end of some verbs in the past absolute: s/he had to, could.

Saturday,August 28, 2021

|

|

FARE-Parte 1

La prima volta che uno studente d’italiano incontra il verbo FARE, in oltre a

mandarlo a memoria perché è irregolare, impara delle altre espressioni: fa caldo,

fa freddo, fare una passeggiata, fare un viaggio, fare la doccia, ecc. Deve

accettare che FARE non ha un solo significato, ma ha anche degli usi idiomatici

particolari che sono più difficili da tradurre. Le frasi idiomatiche sono quelle che

hanno un significato diverso da quello letterale delle singole parole.

Consideriamo questi esempi:

The first time a student of Italian encounters the verb FARE, in addition to

memorizing it because it is irregular, she learns several other expressions: it’s

hot, it’s cold, take a walk, take a trip, take a shower, etc. She must accept that

the verb FARE does not have only one meaning; it also has specific idiomatic

uses that are more difficult to translate. Idiomatic expressions are those that

have a different meaning from the literal significance of each single word.

Let’s consider these examples:

| fare carriera |

to be |

| successful |

not to make a career |

| fare benzina |

to get |

| gas |

not refine it |

| fare colpo su qualcuno |

to impress |

| someone |

not hit them over the head |

| fare un regalo |

to give a |

| gift |

not manufacture it |

| fare due chiacchiere |

to |

| chat |

not make two gossips |

| fare presto |

to hurry |

| up |

not to make early |

| fare i biglietti |

to purchase |

| tickets |

not print them |

| fare la seconda media |

to be the 7th |

| grade |

not make the 2nd average |

| fare lo sci |

to |

| ski |

not build one |

Saturday, July 31, 2021

|

|

| |

|

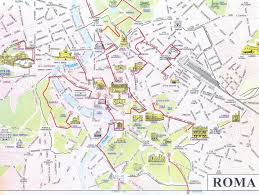

CARTA/MAPPA/CARTINA=PAPER/MAP: Parte II

Vi state preparando per un viaggio in Italia? O siete appena arrivate in una

nuova città italiana? Siete persi? Entrate in un ufficio turistico e cosa chiedete:

una carta, una mappa, una pianta, una cartina, uno schema?

La parola “carta” non si traduce in inglese solo come: “paper”, può anche

significare una cartina, una mappa, un documento, un certificato, un foglio di

carta.

Consideriamo gli altri tipi diversi di “carta” secondo il loro uso, ricordando quello

che abbiamo visto la settimana scorsa:

1. Carte fisiche: sono simili a quelle topografiche; riportano i dettagli del

territorio: montagne, colline, fiumi, laghi, coste, città, paesini, ecc.

2. Carte tematiche: descrivono una zona in base a un aspetto particolare.

3. Carte escursionistiche: mostrano sentieri e punti di riferimento utili per

orientarsi.

4. Planisfero: la mappa della superficie terrestre.

Ma per ora basta dire: “Ha una mappa/pianta dell’Italia?” oppure “Ha una

piantina/cartina di Roma che riporta tutte le strade?”

BUON VIAGGIO!

Are you getting ready for a trip to Italy? Did you just arrive in a new Italian city?

Are you lost? What do you ask for when you enter into a tourist office?

The word “carta” is not translated into English as merely “paper”, it can also

mean a city plan, a map, a document, a certificate, a sheet of paper.

Let’s take a look at other different types of “carte” according to their use,

keeping in mind what we saw last week:

1. Physical maps are similar to topographical ones and show territorial details:

mountains, hills, rivers, lakes, coastline, cities, small town, etc.

2. Thematic maps: describe an area based upon a particular aspect.

3. Hiking maps show trails and points of reference that are useful to orient

oneself.

4. Planisphere: a world map showing the surface of the earth.

For now, it is enough to say; “Do you have a map of Italy?” or “Do you have a

street map of Rome?”

HAVE A GREAT TRIP!

Saturday, July 24, 2021

|

|

CARTA/MAPPA/CARTINA=PAPER/MAP: Parte I

Vi state preparando per un viaggio in Italia? O siete appena arrivate in una

nuova città italiana? Siete persi? Entrate in un ufficio turistico e cosa chiedete:

una carta, una mappa, una pianta, una cartina, uno schema?

La parola “carta” non si traduce in inglese solo come: “paper”, può anche

significare una cartina, una mappa, un documento, un certificato, un foglio di

carta.

Consideriamo i tipi diversi di “carta” secondo il loro uso:

1. Piante e mappe: sono usate per rappresentare case, quartieri, città; a volte

riportano l’indicazione stradale e le linee di trasporto.

2. Carte topografiche: sono piene di dettagli che descrivono piccole zone

territoriali.

3. Carte stradali o corografiche: rappresentano territori regionali e contengono l

e informazioni più importanti riguardanti le vie e le strade.

4. Carte politiche o amministrative: spesso a colori, riportano i confini sia

regionali sia nazionali.

Ma per ora basta dire: “Ha una mappa/pianta dell’Italia?” oppure “Ha una

piantina/cartina di Roma che riporta tutte le strade?”

Riprendiamo la settimana prossima.

Nel frattempo vi auguro: BUON VIAGGIO!

Are you getting ready for a trip to Italy? Did you just arrive in a new Italian city?

Are you lost? What do you ask for when you enter into a tourist office?

The word “carta” is not translated into English as merely “paper”, it can also

mean a city plan, a map, a document, a certificate, a sheet of paper.

Let’s take a look at different types of “carte” according to their use:

1. “Piante” and “mappe” describe houses, neighborhoods, cities; at times they

show the way roads are traveled or public transportation routes.

2. Topographical maps: are full of details that describe small land areas.

3. Street or chorographic maps show regional areas and contain the most

important information regarding streets and roads.

4. Political or administrative maps: often in color, they show the bot regional

and national borders.

For now, it is enough to say; “Do you have a map of Italy?” or “Do you have a

street map of Rome?”

We will pick up where we left off next week.

Meanwhile, HAVE A GREAT TRIP!

Saturday, July 17, 2021

|

|

TO RENT

Ci sono due parole diverse in italiano.

Si affitta un immobile ma si noleggia un veicolo o un oggetto.

Esempi con affittare:

1. Abbiamo preso in affitto una casa al mare per il mese di luglio.

2. Gli affitti a San Francisco sono così alti che è difficile viverci.

3. Hai pagato l’affitto dello studio, oggi è il primo del mese.

4. Quando Lucrezia è partita di casa, i suoi genitori hanno dato in affitto la sua

camera da letto.

Esempi con noleggiare:

1. I ragazzi hanno noleggiato un furgone per trasportare i loro mobili.

2. Quando vado in Italia, prendo in noleggio un’automobile direttamente

all’aeroporto, anche se a volte costa di più, è molto comodo.

3. Avete noleggiato del materiale fotografico per il vostro progetto.

In Italian, there are two different words for “rent”. You rent (AFFITTARE)

a property, but you rent (NOLEGGIARE) a vehicle or an object.

Examples with AFFITTARE:

1. We rented a house at the shore for the month of July.

2. The rents are so high in San Francisco that it is difficult to live there.

3. Did you pay the office rent; today is the first of the month?

4. When Lucrezia left home, her parents rented out her bedroom.

Examples with NOLEGGIARE:

1. The boys rented a truck to move their furniture.

2. When I go to Italy, I rent a car directly at the airport; even if at times

it costs more, it is very convenient.

You rented some photographic equipment for your project.

Saturday, July 10, 2021

|

|

TO COOK = CUCINARE O CUOCERE?

Quante volte sento la domanda: “Qual è la differenza tra CUCINARE e CUOCERE?”

In inglese si traducono con la stessa parola.

CUCINARE: verbo transitivo/regolare

1. Preparare e cuocere una vivanda: Cucinare la carne;

2. Cucinare un articolo, nel gergo giornalistico, preparare uno scritto alla

pubblicazione.

3. In senso figurato: trattare qualcuno in un certo modo: Il caporeparto l’ha

cucinato a dovere.

• è entrato a far parte del lessico nel secolo XI • è entrato a far parte del lessico nel secolo XI

CUOCERE: verbo transitivo/irregolare: indicativo presente: cuòcio, cuòci, cuòce,

cuociamo, cuocete, cuòciono; passato remoto: còssi, cocésti, còssero; congiunt.

cuòcia, cociamo, cociate, cuòciano; participio passato còtto o cociuto

1. Sottoporre a cottura, trattare col calore sostanze varie per ottenere un

cambiamento delle loro caratteristiche: cuocere la carne, l'argilla.

2. In senso figurato: lasciare cuocere qualcuno nel suo brodo.

3. Bruciare, scottare qualcosa, specialmente una parte del corpo; frequentemente

con specificazione della persona: Quando vado al mare il sole mi cuoce la pelle.

4. Seccare, inaridire qualcosa: Il riscaldamento globale cuoce la terra in molte parti

del mondo.

5. In senso figurato: non dare pace, tormentare: L’insulto gli cuoce ancora adesso.

• è entrato a far parte del lessico nel secolo XIII • è entrato a far parte del lessico nel secolo XIII

TO COOK = CUCINARE O CUOCERE?

How often I hear the question: “What’s the difference between ‘cucinare’ and

‘cuocere’? They both mean to cook don’t they?”

CUCINARE is a regular transitive verb, it means:

1. to prepare or cook food: cook meat;

2. in the language of newspapers, to cook means to prepare an article for

publication;

3. in a figurative sense: Deal with someone in a certain way: His boss

really cooked his goose!

• This word entered the Italian lexicon in the 11th century. • This word entered the Italian lexicon in the 11th century.

CUOCERE: is an irregular transitive verb, it means:

1. Apply heat to varied

materials, in order to change their characteristics: to cook

meat, or bake clay.

2. In

a figurative sense: leave someone cooking in his own broth, not caring about

him=let him stew in his own juice.

3. Burn something, usually a part of the body: When I go to the beach the sun

cooks (bakes) my skin.

4. Dry, parch: Global warming cooks/bakes the soil in many parts of the earth.

5. In a figurative sense: not to give peace, to torment: The insult continues to cook

(away at) him even now.

•This word entered the Italian lexicon in the 13th century. •This word entered the Italian lexicon in the 13th century.

Saturday, July 03, 2021

|

|

METTERCI--

La settimana scorsa abbiamo esaminato i vari usi del verbo “volerci”. Oggi

indirizziamo una forma verbale che ha legami simili quando si parla di traduzione

in inglese.

Perciò "metterci" quando è usato nel contesto di tempo significa “impiegare un

periodo di tempo determinato”.

Esempi:

- Quanto ci mette il treno per andare da Roma a Firenze? Ci mette almeno un

paio d’ore.

- A volte Luisa ci mette un po' a capire quello che deve fare.

- Perché ci hai messo tanto tempo per finire i compiti? Non erano difficili.

- L'architetto ci ha messo solo alcuni giorni per finire il progetto della sala

d’esposizione.

- Come mai ci avete messo tanto tempo ad arrivare, abitate a due passi?

"Metterci" però ha anche altri usi e significati, alcuni esempi sono:

- Ti sei ricordato di metterci il sale, ieri l’arrosto era sciapo?

- Anche se ce l’hanno messa tutta, non sono riusciti a vincere la partita.

- Finalmente ho deciso di metterci una pietra sopra.

- Una persona seria non si vergogna di metterci la faccia per una giusta causa.

- Mettiamoci d’accordo una volta per sempre.

Last week we looked at the various uses of the verb “volerci”. Today we will

address a verb that has similar ties when we are dealing with the English

translation.

Therefore, "metterci" when it is used in the context of time means, “requiring a

specific period of time”.

Examples:

- How much time does the train take to go from Rome to Florence? It takes at

least a couple of hours.

- At times, it takes Luisa a little while to understand what she needs to do.

- Why did you take so much time to finish your homework? It wasn’t difficult.

- The architect took only a few days to finish the project for the exhibition hall.

- Why did it take you so much time to get here, you live around the corner?

"Metterci" however can have other uses and meanings, a few examples are:

- Did you remember to put in the salt, yesterday the roast was tasteless?

[meaning to “add”]

- Even if they put everything they had into it, they weren’t able to win the

match.

- I finally decided to bury it. [literally translated: to put a stone over it]

- A serious person isn’t afraid to put his best foot forward for a just cause.

[literally translated: to put his face out there]

- Let’s agree once and for all.

Saturday, June 26, 2021

|

|

VOLERCI—cosa significa e come si usa?

Quando il verbo esprime necessità, la cosa necessaria è sottintesa, per esempio

tempo, quantità, ecc. Perciò, il verbo è spesso coniugato alla terza persona

singolare o plurale.

Esempi:

- Domanda: Quanto ci vuole per andare da Roma a Firenze in treno? (Qui, la

cosa sottointesa è il tempo, perciò il verbo è alla terza persona singolare.)

Risposta: Ci vogliono almeno un paio d’ore. (Qui, siccome parliamo di ore, il

verbo è alla terza persona plurale.)

- Domanda: Quanti ci vogliono per fare un tiramisù?

Risposta: Ce ne vogliono una ventina. (Qui, la cosa sottintesa sono i

biscotti, perciò il verbo è alla terza persona plurale.)

Altre frasi che usano questa forma verbale sono:

- Ieri perdo la borsetta e oggi mi rubano il telefonino. Non ci voleva anche

questa!

- Non ci vuole molto a capire che Lorenzo è un genio.

- Ce n’è voluto di sforzo, ma finalmente siamo riusciti a scalare la montagna.

- Ti ci vogliono altri due giorni di ferie per riprenderti completamente.

La morale: Non è facile tradurre da una lingua all’altra; questo è il perché la

traduzione è un’arte e non una scienza.

VOLERCI—what does it mean and how is it used?

When the verb expresses necessity, the needed item is implied, for example time,

quantity, etc. Therefore, the verb is often in the third person singular or plural.

Examples:

- Question: How long does it take to go from Rome to Florence by train? (Here

the implied item is time, thus the verb is in the third person singular.)

Answer: It takes at least a couple of hours. (Here, since we are talking

about hours, the verb is in the third person plural.)

- Question: How many are needed to make a tiramisu?

Answer: About twenty (are needed). (Here the implied items are the

cookies, thus the verb is in the third person plural.)

Other sentences that use this verbal form are:

- Yesterday I lost my purse and today they steal my cellphone. That’s all I

needed!

- It doesn’t take much to understand that Lawrence is a genius.

- It took a great deal of effort, but finally we were able to scale the mountain.

- You need two more days off in order to recover completely.

The moral: It isn’t easy translating from one language to another; this is why

translation is an art and not a science.

Saturday, June 19, 2021

|

|

Parole che confondono: TASSO

I miei studenti mi insegnano molto, per fortuna. Parole che diamo per scontato in

italiano confondono perché sono troppo simili. Abbiamo già visto questi esempi:

tassa (femminile singolare) = tax, levy, or duty/burden or onus

tazza (femminile singolare) = cup or cupful

tasca (femminile singolare) = pocket, bag or pouch

tassì (maschile singolare) = taxi or cab

tosse (femminile singolare) = cough

Adesso incominciamo a esaminare TASSO (maschile singolare) che ha molti

significati. Incominciamo con questi:

un piccolo mammifero  = badger = badger

pelle dello stesso animale = badger fur

albero delle conifere = yew tree

legno dell’albero = yew wood

misura o indice = rate

per esempio: Il tasso d’umidità è così basso che c’è pericolo d’incendi. per esempio: Il tasso d’umidità è così basso che c’è pericolo d’incendi.

For example: The humidity rate is so low, that there is danger of fires.

interesse bancario = interest rate interesse bancario = interest rate

per esempio: Questi giorni il tasso su un mutuo è molto basso, vale

proprio la pena. proprio la pena.

For example: These days the interest rate on a mortgage is very low, it’s

really worth it. really worth it.

CONFUSING WORDS: TASSO

My students teach me a lot, thank goodness. Words that we take for granted in

Italian can be confusing because they are too similar among themselves. Listed

above are some examples we have already looked at in the past.

Today we will begin by looking at TASSO (masculine/singular) since it has many

meanings. Let’s begin with these:

Saturday, June 12, 2021

|

| |

|

POWER—Parte 4

Come abbiamo già visto, ci sono diversi modi di tradurre la parola inglese

“power” in italiano. I termini più comuni sono: forza, potenza e potere. Li

esamineremo, uno alla volta; oggi tocca a potere!

Vi inoltro—con riconoscenza—queste osservazioni che provengono

dall’articolo: Forza, potenza e potere di A. Bertirotti e V. Succi - marzo 2012

Riflessioni.it

Si prenda ora, e per ultimo, il termine potere:

· Avere la capacità, la possibilità, il permesso, il diritto di fare qualche

cosa; cosa;

· Essere lecito o consentito;

· Essere possibile o probabile;

· Esprime un desiderio o un dubbio;

· Essere efficace, avere forza;

· Facoltà concreta di fare o non fare qualche cosa;

· Capacità di influire su persone;

· Funzione affidata per legge al titolare di una carica;

· Balia, dominio esercitato sugli altri;

· Esercizio dell’autorità in un determinato campo;

· La suprema autorità politica dello Stato;

· Proprietà di un corpo o sistema di produrre determinati fenomeni.

As we have already said, there are various ways to translate the English

word “power” into Italian. The most common forms are “forza”, “potenza”

and “potere”. We will review them one at a time; today it is the turn of

“potere”.

I am forwarding these findings—with my thanks—from the article: Forza,

potenza e potere di A. Bertirotti e V. Succi - marzo 2012 Riflessioni.it

POTERE means:

· To have the capacity, the possibility, the permission, the right to do

something; something;

· To be lawful or permitted;

· To be possible or probable;

· It expresses a desire or a doubt;

· To be effective, to have strength;

· The concrete ability to do or not do something;

· The ability to influence other;

· The function given by law to an appointed official;

· The power or control over others;

· The exercise of authority in a specific field;

· The supreme political authority of the Government;

· The ability of a body or system to produce specified phenomena.

Saturday, June 5, 2021

|

|

POWER—Parte 2

Come abbiamo già visto, ci sono diversi modi di tradurre la parola inglese

“power” in italiano. I termini più comuni sono: forza, potenza e potere. Li

esamineremo, uno alla volta; oggi tocca a potenza!

Vi inoltro—con riconoscenza—queste osservazioni che provengono

dall’articolo: Forza, potenza e potere di A. Bertirotti e V. Succi - marzo 2012

Riflessioni.it

Il termine potenza significa:

· Potere o forte influenza, specialmente a livello politico ed economico;

· Vigore, grande forza fisica;

· Intensità di un fenomeno;

· Violenza, vigore di un impatto;

· Proprietà di fornire determinate prestazioni o certi effetti;

· Nazione che svolge un ruolo determinante a livello nazionale;

· Industria che ha un ruolo preminente in un settore;

· Lavoro compiuto nell’unità di tempo da una macchina;

· Il numero che si ottiene moltiplicando la base per se stessa per il

numero di volte indicato dall'esponente.

As we have already said, there are various ways to translate the English

word “power” into Italian. The most common forms are “forza”, “potenza”

and “potere”. We will review them one at a time; today it is the turn of

“potenza”.

I am forwarding these findings—with my thanks—from the article: Forza,

potenza e potere di A. Bertirotti e V. Succi - marzo 2012 Riflessioni.it

POTENZA means:

· Power or strong influence, especially at the political and economic

levels; levels;

· Vigor, great physical strength;

· The intensity of a phenomenon;

· Violence, the strength of an impact;

· The capability to provide specific features or certain effects;

· A nation that performs a specific function at the national level;

· An industry that predominates in a sector;

· Work carried out by a machine in a specified time period;

· The number that results from multiplying its base by itself, times the

number of the exponent—“to the power of”. number of the exponent—“to the power of”.

Saturday, May 29, 2021

|

|

POWER—Parte 2

Come abbiamo già visto, ci sono diversi modi di tradurre la parola inglese

“power” in italiano. I termini più comuni sono: forza, potenza e potere. Li

esamineremo, uno alla volta; oggi tocca a Forza!

Vi inoltro—con riconoscenza—queste osservazioni che provengono

dall’articolo: Forza, potenza e potere di A. Bertirotti e V. Succi - marzo 2012

Riflessioni.it

Tornando al nostro termine, con forza si intendono:

· Energia, vigore fisico ed intellettuale;

· Causa che modifica lo stato di quiete o di moto di un corpo;

· Potenza, impeto, furia, veemenza di un elemento naturale;

· Determinazione, risolutezza, fermezza morale o di carattere;

· Coraggio, audacia, capacità di affrontare difficoltà;

· Potenzialità, possibilità;

· Truppe, milizie, contingente;

· Gruppo di persone che svolgono un’attività comune o esercitano potere.

POWER—Part 2 POWER—Part 2

As we have already said, there are various ways to translate the English

word “power” into Italian. The most common forms are “forza”, “potenza”

and “potere”. We will review them one at a time; today it is the turn of

“forza”.

I am forwarding these findings—with my thanks—from the article: Forza,

potenza e potere di A. Bertirotti e V. Succi - marzo 2012 Riflessioni.it

FORZA means:

Energy, physical and intellectual stamina;

That which alters the state of calm or movement of a body;

Power, impetus, fury, vehemence of a natural element;

Determination, resoluteness, moral steadfastness or of character;

Courage, nerve, ability to confront difficulties;

Potentiality, possibility;

Troops, militia, military contingent;

Group of individuals who carry out a common activity or exercise power.

Saturday, May 22, 2021

|

|

ONORIFICENZE ITALIANE:

NOBILTÀ: Come parte della Costituzione repubblicana, entrata in vigore in

Italia il 1° gennaio 1948, i titoli nobiliari cessano di essere riconosciuti

dalla legge (anche se, in senso stretto, non sono aboliti o vietati), e

l'organo di Stato che li aveva regolati, la Consulta Araldica, è eliminato.

Tuttavia i cosiddetti predicati - denominazioni territoriali o feudali - che

erano stati spesso collegati a un titolo nobiliare con l'uso di una particella

nobiliare, come di, da, della, dei, potrebbe essere ripresa come parte del

cognome legale dopo l'approvazione giudiziaria per le persone che lo

possedevano prima del 28 ottobre 1922 (data dell’ascesa al potere del

fascismo italiano). In pratica, ciò significa che, ad esempio, "Sempronio,

Duca di Tale Paese" o "Tizia, Principessa del Regno" potrebbero diventare

“Sempronio di Tale Paese " o " Tizia del Regno", rispettivamente. Tuttavia, i

titoli vengono spesso ancora utilizzati ufficiosamente in villaggi, club privati

e gruppi sociali. Signore e Signora (che indicavano aristocrazia terriera) sono

traduzioni di "Lord" e "Lady", usati anche nella gerarchia militare e per le

persone in posizioni ufficiali o per i membri dell’élite di una società. Alcuni

titoli sono comuni anche in forma diminutiva come termini di affetto per i

giovani (ad esempio per Principino o Contessina).

I titoli nobili sono:

- Re / Regina

- Principe / Principessa

- Duca / Duchessa

- Marchese / Marchesa

- Conte / Contessa

- Visconte / Viscontessa

- Barone / Baronessa

- Coscritto / Coscritta

- Patrizio / Patrizia

- Nobiluomo / Nobildonna

- Cavaliere Ereditario (non esiste un equivalente femminile)

ITALIAN TITLES:

NOBILITY: As part of the republican constitution that came into effect in

Italy on January 1, 1948, titles of nobility ceased to be recognized by law

(although they were not, strictly, abolished or banned), and the organ of

state which had regulated them, the Consulta Araldica, was eliminated.

However the so-called predicati — territorial or manorial designations—

that were often connected to a noble title by use of a word such as di, da,

della, dei, could be taken up again as part of the legal surname upon

judicial approval for persons who possessed it prior to October 28, 1922

(date of the Fascist accession to power in Italy). This meant that, for

example, "John Doe, Duke of Somewhere" or "Jane Doe, Princess of the

Kingdom" might become "John Doe of Somewhere" or "Jane Doe of

Kingdom", respectively. Nonetheless, titles are often still used unofficially

in villages, private clubs and some social settings. Signore and Signora

(formerly signifying landed nobility) are translations of "Lord" and "Lady",

used also in the military hierarchy and for persons in official positions or for

members of a society's elite. A few titles are also common in diminutive

form as terms of affection for young people (e.g. Principino for "Little Prince"

or Contessina for "the Little Countess").

The noble titles are:

- Re (King) / Regina (Queen)

- Principe (Prince) / Principessa (Princess)

- Duca (Duke) / Duchessa (Duchess)

- Marchese (Marquis) / Marchesa (Marchioness)

- Conte (Count or Earl) / Contessa (Countess)

- Visconte (Viscount) / Viscontessa (Viscountess)

- Barone (Baron) / Baronessa (Baroness)

- Coscritto (Select) / Coscritta

- Patrizio (Patrician) / Patrizia

- Nobiluomo (Nobleman) / Nobildonna (Noblewoman)

Cavaliere Ereditario (Baronet) (there is no female equivalent)

Saturday, May 15, 2021

|

|

POWER—Parte 1

Ci sono diversi modi di tradurre il termine inglese “power” in italiano. I modi

più comuni sono: forza, potenza e potere. Li esamineremo e li

impareremo, uno alla volta, ma per adesso iniziamo con questi altri

significati.

1. Alimentare: Il vento alimenta (fornisce energia) al generatore elettrico.

2. Capacità: Aveva la capacità di fare innamorare chiunque incontrasse.

3. Corrente: Durante gli incendi in California, ai cittadini di Los Angeles è

mancata la corrente per qualche giorno. mancata la corrente per qualche giorno.

4. Energia elettrica: La batteria del cellulare ha ancora un po’ di carica.

5. Matematica: Due alla terza potenza fa otto.

6. Ottica: Ingrandimento: Quella lente ha 20 ingrandimenti.

POWER—Part 1

There are varied ways to translate the English term “power” into Italian.

The most common forms are “forza”, “potenza” and “potere”. We will

examine and learn them, one at a time, but for now, we will begin with

these other meanings.

1. Supply: Wind powers the electrical generator.

2. Capacity: He had the power to make anyone he met fall in love with

him. him.

3. Electric current: During the fires in California, the citizens of Los

Angeles lost electric power for several days. Angeles lost electric power for several days.

4. Energy: The cell phone battery still has some power.

5. Mathematics: Two to the power of three is eight.

6. Optics: Enlarge: That lens has the power to magnify twenty times.

Saturday, May 8, 2021

|

|

PAROLE CHE CONFONDONO:

I miei studenti mi insegnano molto, per fortuna. Parole che diamo per

scontato in italiano, confondono perché sono troppo simili tra di loro. Ecco

degli esempi:

tassa (femminile singolare) tasso * = tax, levy, or duty/burden or onus

tazza (femminile singolare) = cup or cupful

tasca (femminile singolare) = pocket, bag or pouch

tassì (maschile singolare) = taxi or cab

tosse (femminile singolare) = cough

*tasso (maschile singolare) —Questa la mettiamo da parte per un’altra

volta, ha troppi significati!

CONFUSING WORDS:

My students teach me a lot, thank goodness. Words that we take for

granted in Italian can be confusing because they are too similar among

themselves. Listed above are some examples.

* tasso (maschile singolare)—This one we will set aside for another time, it

has too many meanings!

Saturday, May 1, 2021

|

|

Qual è l’origine del nome BOCCE? Chi dice “bacio” e chi “bocciare”, così

mi sono incuriosita. Il risultato è questo:

L’etimologia della parola è incerta (tanto per cambiare)!

Il Vocabolario etimologico della lingua italiana di Ottorino Piangiani dice

che la parola origina: (a) dal latino Bauca o Bòcia, un tipo di vaso

rotondo a collo stretto di solito di vetro; o, (b) dall’antico tedesco Bossel

per una cosa gonfia.

Il gioco stesso risale al 7000 a.C. in Turchia. Ci sono rappresentazioni

pittoriche in Egitto e in Grecia, ne parla Omero nell’Iliade, e agli scavi di

Pompei sono state ritrovate otto bocce e un pallino. I legionari romani

portano il gioco in Gallia e fino in Inghilterra. Eventualmente il gioco si

diffonde per tutta l’Europa. In Italia, “nel 1753 a Bologna uscì un

manuale, il Gioco delle bocchie di Raffaele Bisteghi, primo esempio di

regolamentazione in lingua italiana.”

Nonostante il gioco non sia né romantico come un bacio né scoraggiante

come essere bocciato, è sempre divertente!

What are the origins of the word BOCCE? (In English, the game is

Boules or Lawn Bowling.) There were those who say “bacio/kiss”

others “bocciare/to flunk” so I became curious. This is the result:

The etymology of the word is uncertain (so what else is new)!

The Vocabolario etimologico della lingua italiana (Etymological

Dictionary of the Italian Language)by Ottorino Piangiani states that the

word originated from: (a) the Latin Bauca or Bòcia, a type of round

vase usually made of glass with a tight neck; or (b) the ancient German

Bossel, something swollen.

The game itself dates back to 7,000 BCE in Turkey. There are pictorial

depictions in Egypt and in Greece; Homer speaks of the game in the

Iliad; at the ruins of Pompeii eight bocce balls and one “pallino” (jack or

cue ball) were discovered. Roman legionnaires brought the game to

Gaul and as far as England. Eventually the game spread throughout all

of Europe. In Italy “in 1753 a manual, the Game of Bocce by Raffaele

Bisteghi was published, it is the first example of regulations in the Italian

language.”

Notwithstanding that the game is neither as romantic as a kiss nor as

discouraging as flunking, it is always fun!

Saturday, April 24, 2021

|

|

“I'm Late, I'm Late

for a very important date,

No time to say hello, goodbye,

I'm late, I'm late, I'm late.”

[From: the Walt Disney Productions animated movie

"Alice in Wonderland" (1951) Music by Sammy Fain /

Lyrics by Bob Hilliard—Dal film d’animazione di Walt

Disney “Alice nel paese delle meraviglie” (1951),

musica di Sammy Fain / parole di Bob Hilliard]

Se voglio esprimere l’idea di “late” in inglese che

parola posso usare in italiano? Ci sono due modi

principali. Questa settimana esaminiamo RITARDO:

ritardo

delay/lateness/tardiness

Ci sono altre espressioni composte con questa parola:

arrivo in ritardo late arrival

di ritardo behind time

essere in ritardo to be late

in ritardo late/delayed

portare un ritardo di to run late/behind schedule

senza (ulteriore) ritardo without (further) delay

Nonostante tutte le espressioni a nostra disposizione,

non possiamo tradurre e rendere giustizia al testo della c

anzone del Coniglio Bianco (o Bianconiglio) nel film di

Walt Disney “Alice nel paese delle meraviglie”:

Sono in ritardo, sono in ritardo,

per un appuntamento molto importante,

non ho tempo di dire salve, arrivederci,

sono in ritardo, sono in ritardo, sono in ritardo.

Saturday, April 17, 2021

|

|

“I'm Late, I'm Late

for a very important date,

No time to say hello, goodbye,

I'm late, I'm late, I'm late”

[From: the Walt Disney Productions animated movie

"Alice in Wonderland" (1951) Music by Sammy Fain /

Lyrics by Bob Hilliard—Dal film d’animazione di Walt

Disney “Alice nel paese delle meraviglie” (1951),

musica di Sammy Fain / parole di Bob Hilliard]

Se voglio esprimere l’idea di “late” in inglese che

parola posso usare in italiano? Ci sono due modi

principali. Questa settimana esaminiamo TARDI:

è tardi it’s late è tardi it’s late

Ci sono altre espressioni composte con questa parola:

al più tardi  at the latest at the latest

dormire fino a tardi  to sleep in/sleep late to sleep in/sleep late

fare tardi  to be/run late to be/run late

meglio tardi che mai  better late than never better late than never

non è mai troppo tardi  it’s never too late it’s never too late

non più tardi di  no later than no later than

più tardi  later later

presto o tardi  sooner or later sooner or later

si fa tardi/si sta facendo tard  it’s getting late it’s getting late

sul tardi  late/later in the day late/later in the day

troppo tardi  too late too late

Per ora vi lascio perché, ieri ho fatto tardi, non ho

potuto dormire fino a tardi questa mattina; si sta

facendo tardi e vorrei postare quest’articolo prima

che si faccia troppo tardi. A più tardi cari amici.

Saturday, April 10, 2021

|

|

COSA SI MANGIA IN ITALIA A PASQUA?

In Italia a Pasqua si mangia la colomba. La ditta Motta, che

crea il panettone nel 1919, deve trovare il modo di sfruttare gli

stessi macchinari e la stessa pasta, e così, negli anni trenta,

nasce la colomba. L’impasto originale è di farina, burro, uova,

zucchero, e buccia d’arancia candita, il tutto coperto da una

ricca glassatura alle mandorle.

In Italy, at Easter time, Italians eat “Colomba” [the Dove]. Motta,

the company that invented the Christmas Panettone in 1919,

found a way to take advantage of the machinery and the recipe by

creating the Easter Colomba. The original dough is made from

flour, butter, eggs, sugar, and candied orange peel, all of which is

topped with a rich coating of rock sugar and almonds.

Saturday, April 3, 2021

|

|

PERCHÉ ALCUNI COLORI SONO VARIABILI E ALTRI NO?

La maggior parte delle volte, i colori sono aggettivi e per questo motivo si

concordano con il nome nel genere e nel numero, come gli aggettivi regolari. Per

esempio si dice: il ragazzo antipatico, la donna italiana, i bambini addormentati,

le nostre amiche simpatiche; il cielo azzurro, la matita gialla, gli zoccoli neri, le

scarpe rosse. Non dimentichiamo: il ragazzo/la ragazza intelligente, i

fazzoletti/le gonne verdi.

Ma, tra gli aggettivi di colore i seguenti sono invariabili:

amaranto, arancio, blu, bordò, cenere, corallo, indaco, lilla, marrone, nocciola,

ocra, rosa, viola. Perché? Questi aggettivi riferiscono a cose: la rosa, il lilla, la

nocciola, il marrone (una varietà di castagna); mentre blu è un monosillabo—

e come tutti i monosillabi non cambia al plurale.

Altrettanto invariabili sono di solito le gradazioni dei colori: le sciarpe possono

essere bianche, rosse, o grigie, ma si dice le sciarpe bianco perla, rosso mattone,

grigio chiaro.

WHY DO SOME COLORS AGREE WITH THE NOUNS THEY MODIFY AND

OTHERS DO NOT?

Most of the time, colors are adjectives, and thus agree in number and gender with

the nouns they modify. (The list above provides examples of masculine and

feminine nouns and adjectives in both singular and plural form.)

However, the following adjectives of color are invariable (they don’t change from

masculine to feminine nor singular to plural):

amaranth (a reddish purple); orange, blue, burgundy, ash, coral, indigo, lilac,

brown, hazelnut, ochre, rose/pink, violet. Why? These adjectives refer to things:

a rose, a lilac plant, a hazelnut, brown (a variety of chestnut); while blue is a

monosyllable—and like all monosyllables, it does not change in the plural.

The same invariability goes for gradations of colors: scarves can be white, red or

gray (all these adjectives are in the feminine plural to agree in number and gender

with scarves), but pearl white, brick red, light gray only have one form.

Saturday, March 27, 2021

|

|

GLI ALTRI SENSI—parte 2:

Le ultime due settimane abbiamo elencato 12 dei 17 sensi. Oggi ne elenchiamo

gli altri sei in ordine alfabetico:

1. Chemio percezione—la percezione di stimoli chimici, in particolare ormonici;

2. Magnetismo—la capacità di percepire campi magnetici (predomina negli

uccelli, ma esiste anche negli esseri umani);

3. Propriocezione o cinestesia—la capacità di riconoscere la posizione del

proprio corpo nello spazio;

4. Stiramento o allungamento—di solito trovati nei polmoni e altri organi

interni;

5. Tensione—dei muscoli; e

6. Termo percezione—la capacità di percepire caldo o freddo o cambiamenti di

temperatura.

During the last two weeks, we listed 12 of the 17 senses. Here is a list of the

other six in alphabetical order, Italian-style:

1. Chemical perception—perception of chemical stimuli, particularly hormonal;

2. Magnetism—the ability to perceive magnetic fields (found mainly in birds,

but it does exist in human beings);

3. Kinesthesia—the ability to recognize the position of one’s body in space;

4. Stretching or lengthening—usually found in the lungs or other internal

organs;

5. Tension—in muscles; and

6. Temperature or thermesthesia—the ability to perceive cold or heat or

changes in temperature.

Saturday, March 20, 2021

|

|

GLI ALTRI SENSI—parte 1:

La settimana scorsa abbiamo elencato i 5 sensi principali e gli organi che

usiamo per provarli. Sono rispettivamente:

1. Il gusto (la lingua);

2. L’olfatto (il naso);

3. Il tatto (la pelle e le mani);

4. L’udito (le orecchie); e

5. La vista (gli occhi).

Ma ci sono 17 sensi in tutto. Oggi ne elenchiamo altri sei in ordine

alfabetico:

1. Dolore—che può essere in tre distinte subcategorie: cutanea—

sulla pelle; somatica—su ossa e giunture; e concernente gli organi interni;

2. Equilibrio—trovato nell’orecchio interno;

3. Fame;

4. Prurito, che è distinto da quello del tatto;

5. Sete; e

6. Tempo.

Last week we listed the 5 main senses and the organs we use to

experience them. They are respectively:

1. Taste (the tongue);

2. Smell (the nose);

3. Touch (the skin and hands);

4. Hearing (the ears); and

5. Sight (the eyes).

However, there are 17 senses in all. Today we will look at six more of

them in alphabetical order, Italian-style:

1. Pain (nociception)—which can be further divided into three distinct

subcategories: cutaneous—on the skin; somatic—in bones and joints; and

having to do with internal organs;

2. Equilibrium or Balance—found in the inner ear;

3. Hunger;

4. Itch, which is independent from touch;

5. Thirst; and Time.

Saturday, March 13, 2021

|

|

|

I SENSI :

| I 5 sensi principali sono: |

l’organo che usiamo: |

| |

|

| 1. Il gusto |

la lingua |

| 2. L’olfatto |

il naso |

| 3. Il tatto |

la pelle e le mani |

| 4. L’udito |

le orecchie |

| 5. La vista |

gli occhi |

Per praticare il vostro italiano, provate a creare frasi con

queste parole. Soprattutto, divertitevi! |

| The 5 main senses are: |

the organ we use: |

| |

|

| 1. Taste |

the tongue |

| 2. Smell |

the nose |

| 3. Touch |

the skin and hands |

| 4. Hearing |

the ears |

| 5. Sight |

the eyes |

| |

|

To practice your Italian, try to form sentences with these

words. Above all, have fun! |

| |

| Saturday, March 6, 2021 |

|

|

L’ALFABETO TELEFONICO E L’ALFABETO FONETICO

Parte IV: Un po’ di geografia

Adesso, ritorniamo al nostro ALFABETO TELEFONICO, imparando dove

si trovano queste città, almeno quelleitaliane.

Non tutte le 20 regioni sono rappresentate. Quali mancano?

La risposta alla domanda che vi ho posto la settimana scorsa è in fondo.

Lettera |

Nome |

Telefonico e geografico |

A |

(a) |

come Ancona—Marche |

B |

(bi) |

come Bari—Puglia o Bologna—Emilia-Romagna |

C |

(ci) |

come Como—Lombardia |

D |

(di) |

come Domodossola—Piemonte |

E |

(é) |

come Empoli—Toscana |

F |

(èffe) |

come Firenze—Toscana |

G |

(gi) |

come Genova—Liguria |

H |

(àcca) |

come hotel (o "acca") |

I |

(i) |

come Imola—Emilia-Romagna |

J |

(i lùnga/iòta) |

come jolly o jersey o Jesolo (o "i lunga") |

K |

(càppa) |

come kursaal o "cappa" |

L |

(èlle) |

come Livorno—Toscana |

M |

(èmme) |

come Milano—Lombardia |

N |

(ènne) |

come Napoli—Campania |

O |

(ò) |

come Otranto—Puglia |

P |

(pi) |

come Palermo--Sicilia o Padova--Veneto |

Q |

(cu/qu) |

come Quarto o Québec o "qu" |

R |

(èrre) |

come Roma—Lazio |

S |

(èsse) |

come Savona—Liguria o Salerno—Campania |

T |

(ti) |

come Torino--Piemonte o Taranto—Puglia |

U |

(u) |

come Udine—Friuli-Venezia Giulia |

V |

(vu/vi) |

come Venezia--Veneto |

W |

(dóppia vu /vu dóppia /

dóppia vi / vi dóppia) |

come Washington o "vu doppia" |

X |

(ics) |

come xilofono o xeres o "ics" |

Y |

(ìpsilon/i grèca) |

come yogurt o York o "ipsilon" |

Z |

(zèta) |

come Zara--Croazia o "zeta" |

LA RISPOSTA: le 8 regioni non incluse sono:

Abruzzo, Basilicata, Calabria, Molise, Sardegna,

Trentino-Alto Adige, Umbria, Valle d’Aosta.

Le 12 regioni rappresentate sono:

Campania, Emilia-Romagna, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Lazio,

Liguria, Lombardia, Marche, Piemonte, Puglia, Sicilia,

Toscana, Veneto.

TELEPHONIC AND PHONETIC ALPHABET

Part IV: A little bit of geography

Now, let us return to our telephonic alphabet to learn where we

can find these cities; at least the Italian ones. Of the 20 regions, not

all of them are represented. Which ones are missing? The answer to

the question I posed last week is below.

THE ANSWER: the 8 regions that have not been included are:

Abruzzo, Basilicata, Calabria, Molise, Sardegna, Trentino-Alto